The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Book of the Feet, by Joseph Sparkes Hall

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Book of the Feet

A History of Boots and Shoes

Author: Joseph Sparkes Hall

Release Date: April 14, 2018 [EBook #56978]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOOK OF THE FEET ***

Produced by Chuck Greif, deaurider and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

A

HISTORY OF BOOTS AND SHOES,

With Illustrations

OF THE

FASHIONS OF THE EGYPTIANS, HEBREWS, PERSIANS, GREEKS, AND

ROMANS, AND THE PREVAILING STYLE THROUGHOUT EUROPE,

DURING THE MIDDLE AGES, DOWN TO THE PRESENT PERIOD;

ALSO,

HINTS TO LAST-MAKERS, AND REMEDIES FOR CORNS, ETC.

B Y J. S P A R K E S H A L L,

Patent-Elastic-Boot Maker to her Majesty the Queen, the Queen Dowager,

and the Queen of the Belgians.

FROM THE SECOND LONDON EDITION,

WITH A HISTORY OF BOOTS AND SHOES IN THE UNITED STATES,

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF EMINENT SHOEMAKERS,

AND CRISPIN ANECDOTES.

N E W Y O R K:

WILLIAM H. GRAHAM, TRIBUNE BUILDINGS,

J. S. REDFIELD, CLINTON HALL.

———

1847.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1847,

By J. S. REDFIELD,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States, in

and for the Southern District of New York.

/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

STEREOTYPED BY REDFIELD & SAVAGE,

13 Chambers Street, N. Y.

/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

The work embraced in the following pages, which has been received with great favor in England, in the fashionable circles, as well as by the trade, the publisher has great confidence will prove attractive and interesting to the American public.

“I have given,” says Mr. Hall, in his preface to the English edition, “the result of my experience, derived from an intimate practical acquaintance with this department of trade for twenty years, and have endeavored to correct much that was bad in form and material, and I trust have not only found fault in many instances with past and present fashions, but have also enforced and provided the remedy. The illustrations of the ancient fashions are all taken from the highest authorities, and I believe may be relied on as historical.{4}”

In addition to the matter in the second London edition, we have subjoined a History of Boots and Shoes in the United States, showing the changes of fashion in this indispensable article of dress; also, numerous biographical sketches of individuals, who, having learned the art of shoemaking, have afterward distinguished themselves by their genius, talents, or worth, and occupied eminent stations among their fellow-men.

The frequency of the development of literary talent among shoemakers has often been remarked. Their occupation, being a sedentary and comparatively noiseless one, may be considered as more favorable than some others to meditation; but perhaps its literary productiveness has arisen quite as much from the circumstance of its being a trade of light labor, and therefore resorted to, in preference to most others, by persons in humble life who are conscious of more mental talent than bodily strength.

To add further to the interest of this volume, we have selected a few pages of anecdotes, and other miscellaneous matters, tending to elucidate this{5} History and account of the “gentle craft;” the members of which may well be proud of such names as their Sherman, Drew, Bloomfield, Gifford, Lee, Sheffey, Worcester, and others, whose memory will long live, as having adorned the various pursuits in which they became eminent.

While this work will prove useful and instructive as presenting, in the biographical sketches, a body of examples showing, how the most unpropitious circumstances have been unable to subdue an ardent desire for the acquisition of knowledge, and the cultivation of a refined taste; the lover of antiquities, and the votary of fashion, will here have their curiosity gratified, in a history of the varied changes which have taken place in an important article of dress, from the pyramidal ages of ancient Egypt, long ere Greece or Rome occupied a space in history, to the present time, when the beauty, taste, and convenience, of modern boots and shoes, combine to establish the superiority of the cordwainers of Europe and America, compared with their predecessors of any nation or age.{6}

| PAGE. | |

| Chap. I.—On the most ancient Covering of the Feet | 7 |

| Chap. II.—The History of Boots and Shoes in England | 30 |

| Chap. III.—On the more modern Forms of foreign Boots and Shoes | 58 |

| Chap. IV.—Commencement of the Trade | 75 |

| Chap. V.—The Structure of the Human Foot, making Lasts, Curing Corns, etc. | 96 |

| Chap. VI.—The Poetry of the Feet, etc. | 112 |

| Chap. VII.—History of Boots and Shoes in the United States | 135 |

| Chap. VIII.—Biographical Sketches of Eminent Shoemakers | 147 |

| Roger Sherman, 147.—Daniel Sheffey, 155.—Gideon Lee, 156.—Samuel Drew, 163.—Robert Bloomfield, 176.—Nathaniel Bloomfield, 181.—William Gifford, 183.—Noah Worcester, 192.—James Lackington, 196.—Joseph Pendrell, 198.—Thomas Holcroft, 199.—Rev. William Carey, D. D., 200.—George Fox, 202.—Rev. James Nichol, 202.—Rev. William Huntington, 203. | |

| Chap. IX.—Crispin Anecdotes, etc. | 204 |

| Patron Saints of Shoemakers.—St. Crispin’s Day.—Cordwainers’ Hall.—Incorporated Shoemakers.—Proverbs.—Anecdotes. |

IF we investigate the monuments of the remotest nations of antiquity, we shall find that the earliest form of protection for the feet, partook of the nature of sandals. The most ancient representations we possess of scenes in ordinary life, are the sculptures and paintings of early Egypt, and these the investigations of travelled scholars from most modern civilized countries have, by their descriptions and delineations, made familiar to us, so that the habits and manners, as well as the costume of this ancient people, have been handed down to the present time, by the work of their own hands, with so vivid a truthfulness, that we feel as conversant with their domestic manners and customs, as with those of any modern nation to which the book of{8} the traveller would introduce us. Not only do their pictured relics remain to give us an insight into their mode of life, but a vast quantity of articles of all kinds, from the tools of the workmen, to the elegant fabrics which once decorated the boudoir of the fair ladies of Memphis and Carnac three thousand years ago, are treasured up in the museums, both public and private, of this and other countries.

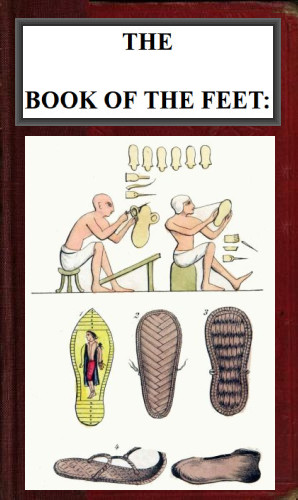

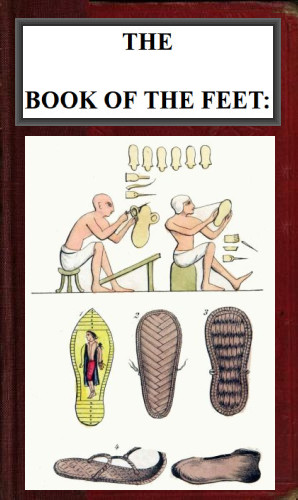

With these materials, it is in no wise difficult to carry our history of shoemaking back to the earliest times, and even to look upon the shoemaker at his work, in the early days of Thothmes the third, who ascended the throne of Egypt, according to Wilkinson, 1495 years before Christ, and during whose reign, the Exodus of the Israelites occurred. The first of our plates contains a copy of this very curious painting, as it existed upon the walls of Thebes, when the Italian scholar Rossellini copied it for his great work on Egypt. The shoemakers are both seated upon low stools (real specimens of such articles may be seen in the British Museum), and are both busily employed, in the formation of the sandals then usually worn in Egypt, the first workman is piercing with his awl the leather thong, at the side of the sole, through which the straps were passed, which secured the sandal to the foot;{9}

before him is a low sloping bench, one end of which rests upon the ground; his fellow-workman is equally busy, sewing a shoe, and tightening the thong with his teeth, a primitive mode of working which is occasionally indulged in at the present day. Above their heads is a goodly row of sandals, probably so placed, to attract a passing customer; the shops in the East being then, as now, entirely open and exposed to every one who passed. As the ancient Egyptian artists knew nothing of perspective, the tools of the workmen that lie around, are here represented above them: they bear, in some instances, a resemblance to those used in the present day; the central instrument, above the man who pierces the tie of the sandal, having the precise shape of the shoemaker’s awl still in use, so very unchanging are articles of utility. In the same manner, the semicircular knife used by the ancient Egyptians three or four thousand years ago, is precisely similar to that of our modern curriers, and is thus represented in a{10} painting at Thebes, of that remote antiquity. The workman, it will be noticed, cuts the leather upon a sloping bench, exactly like that of the shoemaker already engraved.

The warmth and mildness of the East, rendered a close, warm shoe unnecessary; and, indeed, in the present day, they partake there more of the character of slippers; and the foot, thus unconfined by tight shoes, and always free in its motion, retained its full power and pliability: and the custom, still retained in the East, of holding a strap of leather, or other substance, between the toes, is represented in the Theban paintings; the foot thus becoming a useful second to the hand.

Many specimens of the shoes and sandals of the ancient Egyptians, may be seen in our national museum. Wilkinson, in his work on the “Manners and Customs” of this people says, “Ladies and men of rank paid great attention to the beauty of their sandals: but on some occasions, those of the middle classes who were in the habit of wearing them, preferred walking barefooted; and in religious ceremonies, the priests frequently took them off while performing their duties in the temple.”

The sandals varied slightly in form; those worn by the upper classes, and by women, were usually{11} pointed and turned up at the end, like our skates, and the Eastern slippers of the present day. Some had a sharp flat point, others were nearly round. They were made of a sort of woven or interlaced work, of palm leaves and papyrus stalks, or other similar materials; sometimes of leather, and were frequently lined within with cloth, on which the figure of a captive was painted; that humiliating position being thought suitable to the enemies of their country, whom they hated and despised, an idea agreeing perfectly with the expression which so often occurs in the hieroglyphic legends, accompanying a king’s name, where his valor and virtues are recorded on the sculptures: “you have trodden the impure Gentiles under your powerful feet.”

The example selected for pl. I., fig. 1, is in the British Museum, beneath the sandal of a mummy of Harsontiotf; and the captive figure is evidently, from feature and costume, a Jew: it thus becomes a curious illustration of scripture history.

Upon the same plate, figs. 3 and 4 delineate two fine examples of sandals formed as above described, of the leaf of the palm. They were brought from Egypt by the late Mr. Salt, consul-general, and formed part of the collection sold in London, after his death, and are now in the British Museum. They are very different to each other in their con{12}struction, and are of that kind worn by the poorer classes; flat slices of the palm leaf, which lap over each other in the centre, form the sole of fig. 2, and a double band of twisted leaves secures and strengthens the edge; a thong of the strong fibres of the same plant is affixed to each side of the instep, and was secured round the foot. The other (fig. 3) is more elaborately platted, and has a softer look; it must in fact have been as a pad to the foot, exceedingly light and agreeable in the arid climate inhabited by the people for whom such sandals were constructed; the knot at each side to which the thong was affixed, still remains.

The sandals with curved toes, alluded to above, and which frequently appear upon Egyptian sculpture, and generally upon the feet of the superior classes, are exhibited in the woodcut here given: and in the Berlin museum, one is preserved of precisely similar form, which has been engraved by Wilkinson, and is here copied, pl. I., fig. 1. It is particularly curious, as showing how such sandals were held upon the feet, the thong which crosses the instep being connected with another, passing{13} over the top of the foot and secured to the sole, between the great toe and that next to it, so that the sole was held firmly, however the foot moved, and yet it allowed the sandal to be cast off at pleasure.

Wilkinson says that “shoes or low boots, were also common in Egypt, but these I believe to have been of late date, and to have belonged to Greeks; for since no persons are represented in the paintings wearing them, except foreigners, we may conclude they were not adopted by the Egyptians, at least in a Pharaonic age. They were of leather, generally of green color, laced in front by thongs, which passed through small loops on either side; and were principally used, as in Greece and Etruria, by women.”

One of the close-laced shoes is given in pl. I., fig. 4, from a specimen in the British museum. It embraces the foot closely, and has a thong or two over the instep, for drawing it tightly over the foot, something like the half-boot of the present day. The sole and upper leather are all in one piece, sewn up the back and down the front of the foot; a mode of construction practised in England, as late as the fourteenth century.

The elegantly-ornamented boot here given, is copied from a Theban painting, and is worn by a{14} gayly-dressed youth from one of the countries bordering on Egypt: it reaches very high, and is a remarkable specimen of the taste for decoration, which thus early began to be displayed upon this article of apparel.

In Sacred Writ are many early notices of shoes, when Moses exhorts the Jews to obedience (Deut. ch. xxix.), he exclaims, “Your clothes are not waxen old upon you, and thy shoe is not waxen old upon thy foot.” In the book of Ruth (chap. iv.) we have a curious instance of the important part performed by the shoe in the ancient days of Israel, in sealing any important business: “Now this was the manner in former time in Israel, concerning redeeming, and concerning changing, for to confirm all things; a man plucked off his shoe, and gave it to his neighbor; and this was a testimony in Israel.” Ruth, and all the property of three other persons, are given over to Boaz, by the act of the next kinsman, who gives to him his shoe in the presence of{15} witnesses. The ancient law compelled the eldest brother, or nearest kinsman by her late husband’s side, to marry a widow, if her husband died childless. The law of Moses provided an alternative, easy in itself, but attended with some degree of ignominy. The woman was in public court to take off his shoe, spit before his face, saying, “so shall it be done unto that man that will not build up his brother’s house:” and probably, the fact of this refusal was stated in the genealogical registers in connexion with his name; which is probably what is meant by his “name shall be called in Israel, the house of him that hath his shoe loosed.” (Deut. xxv.) The editor of Knight’s Pictorial Bible, who notices these curious laws, also adds that the use of the shoe in the transactions with Boaz, are perfectly intelligible; the taking off the shoe, denoting the relinquishment of the right, and the dissolution of the obligation in the one instance, and its transfer in the other. The shoe is regarded as constituting possession, nor is this idea unknown to ourselves, in being conveyed in the homely proverbial expression by which one man is said to “stand in the shoes of another,” and the vulgar idea of “throwing an old shoe after you for luck,” is typical of a wish, that temporal gifts or good fortune may follow you. The author last quoted says, that{16} even at the present time, the use of the shoe as a token of right or occupancy, may be traced very extensively in the East; and however various and dissimilar the instances may seem at first view, the leading idea may be still detected in all. Thus among the Bedouins, when a man permits his cousin to marry another, or when a husband divorces his runaway wife, he usually says, “She was my slipper, I have cast her off.” (Burckhardt’s “Bedouins,” p. 65.) Sir F. Henniker, in speaking of the difficulty he had in persuading the natives to descend into the crocodile mummy pits, in consequence of some men having lost their lives there, says: “Our guides, as if preparing for certain death, took leave of their children; the father took the turban from his own head, and put it upon that of his son; or put him in his place, by giving him his shoes, ‘a dead man’s shoes.’” In western Asia, slippers left at the door of an apartment, denote that the master or mistress is engaged, and no one ventures on intrusion, not even a husband, though the apartment be his wife’s. Messrs. Tyerman and Bennet, speaking of the termagants of Benares, say, “If domestic or other business calls off one of the combatants before the affair is duly settled, she coolly thrusts her shoe beneath her basket, and{17} leaves both upon the spot, to signify that she is not satisfied;” meaning to denote by leaving her shoe, that she kept possession of the ground and the argument during her unavoidable absence.

From all these instances, it would appear that this employment of the shoe, may, in some respects, be considered analogous to that which prevailed in the middle ages, of giving a glove as a token of investiture, when bestowing lands and dignities.

It should be observed that the same Hebrew word (naal), signifies both a sandal and a shoe, although always rendered shoe in our translation of the Old Testament. Although the shoe is mentioned in Genesis and other books of the Bible, little concerning its form or manufacture can be gleaned—that it was an article of common use among the ancient Israelites, we may infer from the passage in Genesis, chap. xiv., verse 23, the first mention we have of this article, where Abraham makes oath to the king of Sodom “that he will not take from a thread even to a shoe-latchet,” thus assuming its common character.

The Gibeonites (Josh. ix. 5-13) “came with old shoes and clouted [mended] upon their feet”—the better to practise their deceit; and therefore they{18} said, “Our shoes are become old by reason of the very long journey.”

Isaiah “walked three years naked and barefoot:” he went for this long period without shoes, contrary to the custom of the people, and as “a wonder unto Egypt and Ethiopia.”

That it became an article of refinement and luxury, is evident from the many other notices given; and the Jewish ladies seem to have been very particular about their sandals: thus we are told, in the Apocryphal book of Judith, although Holofernes was attracted by the general richness of her dress and personal ornaments, yet it was “her sandals ravished his eyes:” and the bride in Solomon’s Song is met with the exclamation, “How beautiful are thy feet with sandals, O prince’s daughter!”

The ancient bas-reliefs at Persepolis, and the neighborhood of Babylon, second only in their antiquity and interest to those of Egypt, furnish us with examples of the boots and shoes of the Persian kings, their nobles, and attendants; and they were executed, as appears from historical, as well as internal evidence, in the days of Xerxes and Darius.

From these sources, we here select the three following specimens. No. 1 is a half-boot, reaching considerably above the ankle; and it is worn by{19}

the attendant who has charge of a chariot, upon a bas-relief now in the British museum, brought from Persepolis by Sir R. Ker Porter, by whom it was first engraved and described in his interesting volumes of travels in that district. No. 2, also from Persepolis, and engraved in the work just quoted, delineates another kind of boot, or high shoe, reaching only to the ankle, round which it is secured by a band, and tied in front in a knot, the two ends of the band hanging beneath it. This shoe is very common upon the feet of these figures, and is generally worn by soldiers or the upper classes: the attendants or councillors round the throne of these early sovereigns, frequently wear such shoes. No. 3, seen upon the feet of personages in the same rank of life, is here copied from a Persepolitan bas-relief, representing a soldier in full costume. It is a remarkably interesting example, as it very clearly shows the transition state of this article of dress, being something between a shoe and a sandal: in fact, a shoe may be considered as a covered sandal; and, in the instance be{20}fore us, the part we now term “upper leather” consists of little more than the lacings of the sandals, rendered much broader than usual, and fastened by buttons along the top of the foot. The shoe is thus rendered peculiarly flexible, as the openings over the instep allow of the freest movement. Such were the forms of the earliest shoes.

Close boots reaching nearly to the knee where they are met by a wide trowser, are not uncommon upon these sculptures, being precisely the same in shape and appearance as those worn by the modern Cossacks. Indeed, there is nothing in the way of boots that may not be found upon the existing monuments of early nations, precisely resembling the modern ones. The little figure here given might pass for a copy of the boots worn by one of the soldiers of King William the Third’s army, and{21} would not be unworthy of uncle Toby himself, yet it is carefully copied from a most ancient specimen of Etruscan sculpture, in the possession of Inghirami, who has engraved it in his learned work the “Monumenti Etruschi;” the original represents an augur, or priest, whose chief duty was to report and explain supernatural signs.

With the ancient Greeks and Romans, the coverings for the feet assumed their most elegant forms; yet in no instance does the comfort of the wearer appear to have been sacrificed, or the natural play of the foot interfered with—that appears to have been especially reserved for “march-of-intellect” days. Vegetable sandals, termed Baxa, or Baxea, were worn by the lower classes, and as a symbol of their humility, by the philosophers and priests. Apuleius describes a young priest as wearing sandals of palm; they were no doubt similar in construction to the Egyptian ones, of which we have already given specimens, and which were part of the required and characteristic dress of the Egyptian priesthood. Such vegetable sandals were, however, occasionally decorated with ornaments to a considerable extent, and they then became expensive. The making of them in all their variety, was the business of a class of men called Baxearii; and these with the Solearii (or makers of the sim{22}plest kind of sandal worn, consisting of a sole with little more to fasten it to the foot than a strap across the instep) constituted a corporation or college of Rome.

The solea were generally worn by the higher classes only, for lightness and convenience, in the house; the shoes (calceus) being worn out of doors. The soccus was the intermediate covering for the foot, being something between the solea and the calceus; it was, in fact, precisely like the modern slipper, and could be cast off at pleasure, as it did not fit closely, and was secured by no tie. This, like the solea and crepida, was worn by the lower classes and country people; and hence, the comedians wore such cheap and common coverings for the feet, to contrast with the cothurnus or buskin of the tragedians, which they assumed, as it was adapted to be part of a grand and stately attire. Hence the term applied to theatrical performers—“brethren of the sock and buskin,” and as this distinction is both ancient and curious, specimens of both are here given from antique authorities. The side and front views of the sock (Nos. 1, 2) are copied from a painting of a buffoon, who is dancing in loose yellow slippers, one of the commonest colors in which the leather used for their construction was dyed. Such slippers were made to{23}

fit both feet indifferently, but the more finished boots and shoes were made for one foot only from the earliest period. The cothurnus (fig. 3) was a boot of the highest kind, reaching above the calf of the leg, and sometimes as far as the knee. It was laced as the boots of the ancients always were, down the front, the object of such an arrangement being to make them fit the leg as closely as possible, and the skin of which they were made was dyed purple, and other gay colors; the head and paws of the wild animal were sometimes allowed to hang around the leg from the upper part of the cothurnus, to which it formed a graceful addition; an example is given upon our 2d plate, fig. 1, which is a side-view of such an ornamented boot, decorated all over with a pattern like the Grecian volute.

The sole of the cothurnus was of the ordinary thickness in general, but it was occasionally made{24} much thicker by the insertion of slices of cork when the wearer wished to add to his height, and thus the Athenian tragedians, who assumed this boot as the most dignified of coverings for the feet, had the soles made unusually thick, in order that it might add to the magnitude and dignity of their whole appearance.

The unchanging nature of a commodious fashion capable of adoption by the lower classes, may be well illustrated by fig. 2, plate II., which delineates the shoe or sandal worn by the rustics of ancient Rome. It is formed of a skin turned over the foot, and secured by thongs passing through the sides, and over the toe, crossing each other over the instep, and secured firmly round the ankle. Any person familiar with the prints of Pinelli, pictures of the modern brigands of the Abruzzi, or the models of the latter worthies in terra-cotta, to be met with in most curiosity-shops, will at once recognise those they wear as being of the same form. The traveller who has visited modern Rome, will also remember to have seen them on the feet of the peasantry who traverse the Pontine marshes; and the older Irish, and the comparatively modern Highlander, both wore similar ones; they were formed of the skin of the cow or deer, with the hair on them, and were held on the feet by

leather thongs. They were the simplest and warmest kind of foot-covering to be obtained, when every man was his own shoemaker.

There was a form of shoe worn at this early time, in which the toes were entirely uncovered, and of which an example is given in plate II., fig. 3. It is copied from a marble foot in the British museum. This shoe appears to be made of a pliable leather, which fits closely to the foot, for it was considered as a mark of rusticity to wear shoes larger than the foot, or which fitted in a loose and slovenly manner. The toes in this instance are left perfectly free; the upper leather is secured round the ankle by a tie, while a thong, ornamented by a stud in its centre, passing over the instep, and between the great and second toes, is secured to the sole in the manner of a sandal. In order that the ankle-bone should not be pressed on or incommoded in walking, the leather is sloped away, and rises around it to a point at the back of the leg.

None but such as had served the office of edile were allowed to wear shoes of a red color, which we may therefore infer to have been a favorite color for shoes, as it appears to have been among the Hebrews, and as it is still in western Asia. The Roman senators wore shoes or buskins of a black color, with a crescent of gold or silver on the top{26} of the foot. The emperor Aurelian forbade men to wear red, yellow, white, or green shoes, permitting them to be worn by women only, and Heliogabalus forbade women to wear gold or precious stones in their shoes, a fact which will aid us in understanding the sort of decoration indulged in by the earliest Hebrew women, of whose example Judith may be quoted as an instance, to which we have already referred.

The Roman soldiers generally wore a simple form of sandal similar to the example given in plate II., fig. 4, and which is a solea fastened by thongs; yet they, in the progress of riches and luxury, went with the times and merged into foppery, so that Philopoemon, in recommending soldiers to give more attention to their warlike accoutrements than to their common dress, advises them to be less nice about their shoes and sandals, and more careful in observing that their greaves were kept bright and fitted well to their legs. When about to attack a hill-fort or go on rugged marches, they wore a sandal shod with spikes similar to that in plate II., fig. 5, and at other times they had soles covered with large clumsy nails like those of fig. 6, which exhibits the sole of a Roman soldier’s sandal, covered with nails, and which was discovered in London some few years ago; it is copied from an en{27}graving in the Archæological album, and the shoe itself, which forms fig. 7, shows the length of these nails, and the way in which the upper leather was constructed of the sandal form, like those of the Persepolitan figures already alluded to. The Greeks and Romans used shoes of this kind as frequently as the early Persians, and in fig. 7, we have an example of such a combination of sandal and shoe as they wore, the upper leather being cut into a series of thongs, through which passes a broad band of leather, which turns not inelegantly round the upper part of the foot, and is secured by passing many times round the ankle and above it, where it is buckled or tied.

The Roman shoes then had various names, and were distinct badges of the position in society held by the wearer. The solea, crepida, pero, and soccus, belonged to the lower classes, the laborers and rustics, the caliga was principally worn by soldiers, and the cothurnus by tragedians, hunters, and horsemen, as well as by the nobles of the country.

The latter kind of boot, in form and color, as we have already hinted, was indicative of rank or office. Those worn by senators we have noticed, and it was a joke in ancient Rome against a man who owed respect solely to the accident of birth or fortune, that his nobility was in his heels. The{28} boots of the emperors were frequently richly decorated, and the patterns still existing upon marble statues, show that they were ornamented in the most elaborate manner. A specimen from the noble statue of Hadrian in the British museum, forms fig. 8, of our plate, and it is impossible to conceive anything of the kind more elegant and tasteful in its decorations. Real gems and gold were employed by some of the Roman emperors to decorate their boots, and Heliogabalus wore exquisite cameos on his boots and shoes. Fig. 9, is a lower kind of boot, of the same make as fig. 3, but beautifully ornamented.

The Grecian ladies, according to Hope, wore shoes or half-boots, laced before and lined with the fur of animals of the cat tribe, whose muzzles or claws hung down from the top.

Ocrea was the name this boot got among the Romans; “Ocreas verdente puella,” (Juv. vi. sat.); which Dryden, ridiculously enough, translated “Spanish leather boots,” a term of his own time, forced to do service sixteen hundred years before.

The barbarous nations with whom the Romans held war, are upon the bas-reliefs of their conquerors, represented in close shoes or half-boots. Thus the Dacians wear the shoe represented in fig. 10, which laced across the instep, and was secured{29} around the ankle with a band and ornamental button or stud. The Gauls wear the shoe given below, of the same form as that worn by our native ancestors when Julius Cæsar made his descent upon the British islands.

BEFORE the arrival of the Saxons, who have transmitted to us many valuable manuscripts abounding in various delineations of their dress and manners, we shall not find much to engage the attention where it is our present object to direct it, the history of the coverings for the feet. There is, however, little doubt that the rude skin-shoes, worn by the native Irish and the country people of Rome, was the simple protection adopted in this country in the earliest times. Shoes of this material are found in all nations half-civilized, and the ease with which they are formed by merely covering the sole with the hide of an animal, and securing it by a thong, must have had the effect of insuring its general use. Naked feet would, however, be preferred in fine weather, and when shoes were worn, they were generally of a close, warm kind, adapted to our climate; the most antique representations of the Gaulish native chiefs,{31} as given on Roman sculpture, and which may be taken as general representations of British chiefs, may be received as good authorities, their resemblance to each other being so striking as to draw from Cæsar a remark to that effect.

The Saxon figures, as given in the drawings by their own hands, to be seen in manuscripts in most of our public libraries, display the costume of this people, from the ninth century downward; and the minute way in which every portion of the dress is given, affords us clear examples of their boots and shoes. According to Strutt, high shoes, reaching nearly to the middle of the legs, and fastened by lacing in the front, and which may also be properly considered as a species of half-boots, were in use in this country as early as the tenth century; and the only apparent difference between the high shoes of the ancients and the moderns, seems to have been that the former laced close down to the toes, and the latter to the instep only. They appear in general to have been made of leather, and were usually fastened beneath the ankles with a thong, which passed through a fold upon the upper part of the leather, encompassing the heel, and which was tied upon the instep. This method of securing the shoe upon the foot, was certainly well con{32}trived both for ease and convenience. Three specimens of shoes are here given from Saxon drawings. The first is the most ancient and curious; it is copied from “the Durham Book,” or book of St. Cuthbert, now preserved among the Cottonian manuscripts in the British museum, and is believed to have been executed as early as the seventh century, by the hands of Eadfreid, afterward bishop of Lindisfarne, who died in 721. It partakes of the nature of shoe and sandal, and with the exception of the buttons down the front, is precisely like the Persepolitan sandal already engraved and described, as well as like the Roman ones constructed on the same model, and it is curious to see how all are formed after this one fashion.

No. 2, is copied from Strutt’s “complete view of the dress and habits of the people of England,” plate XXIX., fig. 16, and which he obtained from the Harleian MS., No. 603. It very clearly shows{33} the form of the Saxon shoe, and the long strings by which it was tied. Fig. 3, delineates the most ordinary kind of shoe worn, with the opening to the toes already alluded to, for lacing it. But little variety is observable in the form of this article of dress among the Saxons; it is usually delineated as a solid black mass, just as the last figure has been here engraved, with a white line down the centre, to show the opening, but quite as generally without it, and these two forms of shoe or half-boot, are by far the most commonly met with, and are depicted upon the feet of noble and royal personages as well as upon those of the lower class.

Strutt remarks that wooden shoes are mentioned in the records of this era, but considers it probable that they were so called because the soles were formed of wood, while the upper parts were formed with some more pliant material: shoes with wooden soles were at this time worn by persons of the most exalted rank; thus, the shoes of Bernard, king of Italy the grandson of Charlemagne, are thus described by an Italian writer, as they were found in his tomb.

“The shoes,” says he, “which covered his feet are remaining to this day, the soles of wood and the upper parts of red leather, laced together with thongs: they were so closely fitted to the feet that{34} the order of the toes, terminating in a point at the great toe, might easily be discovered; so that the shoe belonging to the right foot could not be put upon the left, nor that of the left upon the right.” It was not uncommon to gild and otherwise ornament the shoes of the nobility. Eginhart describes the shoes worn by Charlemagne on great occasions, as set with jewels.

The Normans wore boots and shoes of equal simplicity, rustics are frequently represented with a half-boot plain in form, fitting close to the foot, but wide at the ankle, like fig. 1, of the group here given, only that in this instance, an ornament consisting of a studded band surrounds the upper part. Such boots were much used by the Normans, and are frequently mentioned by the ancient historians; they do not appear to have been confined to any particular classes of the people, but were worn by persons of all ranks and conditions, as well of the clergy as of the laity, especially when they rode on horseback. The boots deline{35}ated in their drawings are very short, rarely reaching higher than the middle of the legs; they were sometimes slightly ornamented, but the boots and shoes of all personages represented in the famous tapestry of Bayeux, are of the same simple form of construction; and this celebrated early piece of needlework was believed to have been worked by the wife of the conqueror, to commemorate his invasion of England and the battle of Hastings. Another form of Norman shoes may be seen in fig. 2, which is more enriched than the last, and it is curious that the ornament adopted is in the form of the straps of a sandal, studded with dots throughout. In the original, the shoe is colored with a thin tint of black, these bands being a solid black, with white or gilded lines and dots. Another example of a decorated shoe, fig. 3, is given from a MS. of the eleventh century, in the British museum, and shows the kind which became fashionable when the Normans, firmly settled in England, began to indulge in luxurious clothing. These shoes were most probably embroidered.

“We are assured by the early Norman historians,” says Strutt, “that the cognomen curta ocrea, or short boots, was given to Robert, the conqueror’s eldest son; but they are entirely silent respecting the reason for such an appellation{36} being particularly applied to him. It could not have arisen from his having introduced the custom of wearing short boots into this country, for they were certainly in use among the Saxons long before his birth: to hazard a conjecture of my own, I should rather say he was the first among the Normans who wore short boots, and derived the cognomen by way of contempt, from his own countrymen, for having so far complied with the manners of the Anglo-Saxons. It was not long, however, supposing this to be the case, before his example was generally followed.” The short boots of the Normans appear at times to fit quite close to the legs; in other instances they are represented more loose and open; and though the materials of which they were composed are not particularized by ancient writers, we may reasonably suppose them to have been made of leather; at least it is certain that about this time, a sort of leathern boots, called bazans, were in fashion; but they appear to have been chiefly confined to the clergy.

“Among the various innovations,” continues Strutt, “made in dress by the Normans during the twelfth century, none met with more marked and more deserved disapprobation than that of lengthening the toes of the shoes, and bringing{37} them forward to a sharp point. In the reign of Rufus, this custom was first introduced; and according to Orderic Vitalis, by a man who had distorted feet, in order to conceal his deformity;” but he adds, “the fashion was no sooner broached, than all those who were fond of novelty thought proper to follow it; and the shoes were made by the shoemakers in the form of a scorpion’s tail.” These shoes were called pigaciæ, and were adopted by persons of every class, both rich and poor. Soon after, a courtier, whose name was Robert, improved upon the first idea, by filling the vacant part of the shoe with tow, and twisting it round in the shape of a ram’s horn; this ridiculous fashion excited much admiration. It was followed by the greater part of the nobility; and the author, for his happy invention, was honored with the cognomen Cornardus or horned. The long pointed shoes were vehemently inveighed against by the clergy, and strictly forbidden to be worn by the religious orders. So far as we can judge from the drawings executed in the twelfth century, the fashion of wearing long-pointed shoes did not long maintain its ground. It was, however, afterward revived, and even carried to a more preposterous extent.

A specimen of the shoes that were worn at this{38} period, and which so excited the ire of the monkish writers, is here given from the seal of Richard, constable of Chester, in the reign of Stephen; in the original the knight is on horseback, the stirrup and spur are therefore seen in our cut.

The effigies of the early sovereigns of England, are generally represented in shoes decorated with bands across, as if in imitation of sandals. They are seldom colored black, as nearly all the examples of earlier shoes in this country are. The shoes of Henry II. are green, with bands of gold. Those of Richard are also striped with gold; and such richly decorated shoes became fashionable among the nobility, and were generally worn by royalty all over Europe. Thus, when the tomb of Henry VI. of Sicily, who died in 1197, was opened in the cathedral of Palermo, on the feet of the dead monarch were discovered costly shoes, whose upper part was of cloth of gold, embroidered with pearls, the sole being of cork, covered with the same cloth of gold. These shoes reached to the ankle, and were fastened with a little button in{39}stead of a buckle. His queen, Constance, who died in 1198, had upon her feet shoes also of cloth of gold, which were fastened with leather straps tied in knots, and on the upper part of them were two openings, wrought with embroidery, which showed that they had been once adorned with jewels. Boots ornamented with gold, and embroidered in elegant patterns, at this time became often worn. King John of England, orders, in one instance, four pair of women’s boots, one of them to be embroidered with circles; and the effigy of the succeeding monarch, Henry III., in Westminster abbey, is chiefly remarkable for the splendor of the boots he wears; they are crossed all over by golden bands, thus forming a series of diamond-shaped spaces, each one of which is filled with a figure of a lion, the royal arms of England. One of these splendid shoes is engraved in plate III., fig. 1.

The shape of the sole of the shoes at this time, may be seen from the cut here given of one found in a tomb of the period, and called that of St. Swithin, in Winchester cathedral. The shoe is engraved in “Gough’s Sepulchral Monuments,{40}” and the person who discovered it in the tomb thus describes it: “The legs of the wearer were enclosed in leathern boots or gaiters sewed with neatness, the thread was still to be seen. The soles were small and round, rather worn, and of what would be called an elegant shape at present; pointed at the toe and very narrow, and were made and fitted to each foot. I have sent the pattern of one of the soles, drawn by tracing it with a pencil from the original itself, which I have in my possession.” Gough engraves the shoe of the natural size in his work, the measurements being ten inches in length from toe to heel, and three inches across the broadest part of the instep. It will be seen that they are as perfectly “right and left,” as any boots of the present day; but as we have already shown, this is a fashion of the most remote antiquity. As these boots are at least as old as the time of John, Shakspere’s description in his dramatized history of that sovereign, of the tailor, who eager to acquaint his friend, the smith, of the prodigies the skies had just exhibited, and whom Hubert saw

is strictly accurate: yet half a century ago, this passage was adjudged to be one of the many proofs of Shakspere’s ignorance or carelessness. Dr.{41} Johnson, ignorant himself of the truth in this point, but yet, like all critics, determined to pass his verdict, makes himself supremely absurd, by saying in a note to this passage, with ridiculous solemnity, “Shakspere seems to have confounded the man’s shoes with his gloves. He that is frighted or hurried may put his hand into the wrong glove, but either shoe will equally admit either foot. The author seems to be disturbed by the disorder which he describes.”

In the “Art Union,” a journal devoted to the fine arts, are a series of notices of the various forms of boots and shoes in Great Britain, by F. W. Fairholt, F. S. A., from which we may borrow the description of the elegant coverings for the feet in use in the reigns of the first three Edwards. Boots buttoned up the leg, or shoes buttoned up the centre, or secured like the Norman shoe in the second figures of the first cut given in this chapter, were common in the days of Edward I. and II. The splendid reign of the third Edward, says Mr. Fairholt, extending over half a century of national greatness, was remarkable for the variety and luxury, as well as the elegance of its costume; and this may be considered as the most glorious era in the annals of “the gentle craft,” as the trade of shoemaking was anciently termed. Shoes and{42} boots of the most sumptuous description are now to be met with in contemporary paintings, sculptures, and illuminated manuscripts. The boot and shoe here engraved from the Arundel MS., No. 83, executed about 1339 (pl. III., figs. 2 and 3), are fine examples of the extent to which the tasteful ornament of these articles of dress was carried. They remind one of the boots “fretted with gold” and embroidered in circles mentioned by John. The greatest variety of pattern and the richest contrasts of color were aimed at by the maker and inventor of shoes at this period, and with how happy an effect the reader may judge, from the examples just given, as well as from the three also engraved in pl. III., Nos. 4, 5, and 6, and which are copied from Smike’s copies of the paintings, which formerly existed on the walls of St. Stephen’s chapel at Westminster, and which drawings now decorate the walls of the meeting-room of the Society of Antiquaries. It is impossible to conceive any shoe more exquisite in design than fig. 4, of our plate. It is worn by a royal personage, and it brings forcibly to mind the rose windows, and other details of the architecture of this period; but for beauty of pattern and splendor of effect this English shoe of the middle ages is “beyond all Greek, beyond all Roman fame,” for their sandals and shoes have{43} not half “the glory of regality contained in this one specimen.” The fifth figure in the same plate is simpler in design but not less striking in effect, being colored (as the previous one is) solid black, the red hose adding considerably to its effect. No. 6, is still more peculiar, and is cut all over into a geometric pattern, and with a fondness for quaint display in dress peculiar to those times, the left shoe is black and the stocking blue, the other leg of the same figure being clothed in a black stocking and a white shoe. The form of this latter one is that usually worn by persons of all classes, of course omitting the elaborate ornament. The shoe was cut very low over the instep, the heel being entirely covered, and a band fastened by a small buckle or button passing round the ankle secured it to the foot.

The boots and shoes worn during the fourteenth century, were of peculiar form, and the toes which were lengthened to a point, turned inward or outward according to the taste of the wearer. In the reign of Richard II., they became immensely long, so that it was asserted they were chained to the knee of the wearer, in order to allow him to walk about with ease and freedom. It was of course only the nobility who could thus inconvenience themselves, and it might have been adopted by{44} them as a distinction; still very pointed toes were worn by all who could afford to be fashionable. The cut here given exhibits the sole of a shoe of this period, from an actual specimen in the possession of C. Roach Smith, F. S. A., and was discovered in the neighborhood of Whitefriars, in digging deep under ground into what must have originally been a receptable for rubbish, among which these old shoes had been thrown, and they are probably the only things of the kind now in existence.

Two specimens of boots of the time of Edward IV., are here given to show their general form at that period. The first is copied from the Royal MS., No. 15, E. 6, and is of black leather, with a{45} long upturned toe; the top of the boot is of lighter leather, and thus it bears a resemblance to the top-boots of a later age, of which it may be considered as the prototype. The other boot, from a print dated 1515, is more curious; the top of the boot is turned down, and the entire centre opens from the top, to the instep, and is drawn together by laces or ties across the leg, so that it bears considerable resemblance in this point to the Cothurnus of the ancients.

Fashion ran at this time from one extreme to the other, and the shoes which were at one time so long at the toe as to be inconvenient, now became as absurdly broad, and it was made the subject of sumptuary laws to restrain both extremes. Thus Edward IV. enacted that any shoemaker who made for unprivileged persons (the nobility being exempted) any shoes or boots, the toes of which exceeded two inches in length, should forfeit twenty shillings, one noble to be paid to the king, another to the cordwainers of London, and the third to the chamber of London. This only had the effect of widening the toes; and Paradin says that they were then so very broad as to exceed the measure of a good foot. This continued until the reign of Mary, who, by a proclamation, prohibited their being worn wider at the toe than six inches.{46}

We have here engraved two specimens of these broad-toed shoes of the time of Henry VIII. No. 1 is copied from the monumental effigy of Katharine, the wife of Sir Thomas Babynton, who died 1543, and is buried in Morley church, near Derby. It is an excellent specimen of the sort of sole preferred by the fashionables of that day. The second cut exhibits a front view of a similarly-made shoe. They were formed of leather, but generally the better classes wore them of rich velvet and silk, the various colors of which were exhibited in slashes at the toes, which were most sparingly covered by the velvet of which the shoe was composed. In the curious full-length portrait of the poetical Earl of Surrey, at Hampton Court, he is represented in shoes of red velvet, having bands of a darker tint placed across them diagonally; which bands are decorated with a row of gold ornaments.

During the reign of Edward VI., a sort of shoe{47}

with a pointed toe was worn, not unlike the modern one. It was of velvet, generally, with the upper classes; of leather, with the poorer ones. The former indulged in a series of slashes over the upper leather, which the others had not. We give here two specimens of these shoes, from prints dated 1577 and 1588; and they will serve to show the sort of form adopted, as well as the varied way in which the slashes of the velvet appeared, and which altered with the wearer’s taste. Philip Stubbes, the puritanical author of the “Anatomy of Abuses,” 1588, declares that the fashionables then wore “corked shoes, puisnets, pantoffles, and slippers, some of them of black velvet, some of white, some of green, and some of yellow; some of Spanish leather, and some of English, stitched with silk and embroidered with gold and silver all over the foot with gewgaws innumerable.” Rich and expensive shoe-ties were now brought into use, and large sums were lavished upon their decorations.{48} John Taylor, the water poet, alludes to the extravagance of those who

The shoe-roses were made of lace, which was as beautiful, costly, and elaborate, as that which composed the ruff for the neck, or ruffles for the wrist. They were elaborately decorated with needlework and gold and silver thread.

During the reign of the first Charles, the boots (which were made of fine Spanish leather, and were of a buff color) became very large and wide at the top. Indeed, they were so wide at times, as to oblige the wearer to stride much in walking, a habit that was much ridiculed by the satirists of the day. There was a print published during this reign of a dandy in the height of fashion whose legs are “incased in boot-hose tops tied about the middle of the calf, as long as a pair of shirt-sleeves, double at the end like a ruff-band: the top of his boots very large, fringed with lace, and turned down as low as his spurs, which jingled like the bells of a morris-dancer as he walked.” These boots were made very long in the toe, thus, of this exquisite we are told, “the feet of his boots were two inches too long.”

The boot-tops at this time were made wide, and{49} were capable of being turned over beneath the knee, which they completely covered when they were uplifted. They were of course made of pliant leather to allow of this—“Spanish leather,” according to Ben Jonson.

During the whole of the Commonwealth large boot-tops of this kind were worn even by the puritans; they were, however, large only, and not decorated with costly lace. The shoes worn were generally particularly simple in their construction and form, and those who did not wish to be classed among the vain and frivolous, took care to have their toes sharp at the point, as a distinction between themselves and the “graceless gallants,” who generally wore theirs very broad.

With the restoration of Charles II. came the large French boot, in which the courtiers of “Louis le grand,” always delighted to exhibit their legs. Of the amplitude of its tops, the woodcut will give{50} an idea, it is copied from one worn by a courtier of Charles’s train, in the engravings illustrative of his coronation. The boot is decorated with lace all round the upper part, and that portion of the leg which the boot encases, seems fitted easily with pliant leather: over the instep is a broad band of the same material, beneath which the spur was fastened; and the heel is high, and toe broad, of all the boots and shoes then fashionable.

A boot of the end of this reign, forms fig. 7, of our third plate, and is copied from a pair which hang up in Shottesbrooke church, Berkshire, above a tomb, in accordance with the old custom, of burying a knight with his martial equipments over his grave, originally consisting of his shield, sword, gloves, and spurs, the boots being a later and more absurd introduction. The pair which we are now describing, are formed of fine buff leather, the tops are red, and so are the heels, which are very high, the toes being cut exceedingly square.

With the great revolution of 1688, and his majesty William III., came in the large jack-boot, and the high-quartered, high-heeled, and buckled shoe, which only expired at the end of the last century. Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick, has one of these jack-boots in his collection of armor, at Goodrich court; and it has been engraved in his work on ancient{51} arms and armor, from which it is copied in plate III., fig. 8. It is a remarkably fine specimen of these inconvenient things, and is as straight and stiff and formal, as the most inveterate Dutchman could wish. The heel it will be perceived is very high, and the press upon the instep very great, and consequently injurious to the foot, and altogether detrimental to comfort. An immense piece of leather covers the instep, through which the spur is affixed, and to the back of the boot, just above the heel, is appended an iron rest for the spur. Such were the boots of the English cavalry and infantry, and in such cumbrous articles did they fight in the low countries, following the example of Charles XII., of Sweden, whose figure has become so identified with them, that the imagination can not easily separate the sovereign from the boots in which he is so constantly painted, and of which a specimen may be seen in his full-length portrait, preserved in the British museum.

A boot was worn by civilians, less rigid than the one last described, the leg taking more of the natural shape, and the tops being smaller, of a more pliant kind, and sometimes slightly ornamented round the edges.

We have here two examples of ladies’ shoes, as worn during the period of which we are discussing.{52}

The first figure, copied from volume 67, of the “Gentleman’s Magazine,” shows the peculiar shape of the shoe, as well as the clog beneath; these clogs were merely single pieces of stout leather, which were fastened beneath the heel and instep, and appear to be only extra hinderances in walking, which must materially have destroyed any little pliancy which the original shoe would have allowed the foot to retain. The second figure is copied from the first volume of “Hone’s Every Day Book,” and that author says, “This was the fashion that beautified the feet of the fair, in the reign of King William and Queen Mary.” Holme, in his “Academy of Armory,” is minutely diffuse on the gentle craft: he engraves the form of a pair of wedges, which he says “is to raise up a shoe in the instep, when it is too straight for the top of the foot;” and thus compassionates ladies’ sufferings: “Shoemakers love to put ladies in their stocks, but these wedges, like merciful justices, upon complaint, soon do ease and deliver them. If the eye turns to the cut—to the cut of the sole,

with the line of beauty adapted by the cunning of the workman’s skill, to stilt the female foot: if the reader behold that association, let wonder cease, that a venerable master in coat armor, should bend his quarterings to the quarterings of a lady’s shoe, and forgetful of heraldic forms, condescend from his high estate to use similitudes.”

This shape, once firmly established, was the prevailing one during the reigns of George I. and II. Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, of plate III., will fully display the different forms and style, adopted by the fashionables of that day. They always wore red heels, at least all persons who pretended to gentility. The fronts of the gentlemen’s shoes were very high, and on gala-days or showy occasions, a buff shoe was worn. The ladies appear to have preferred silk or velvet to leather: thus fig. 10 is entirely made of a figured blue silk, and it has bright red heels and silver buckles. Fig. 11 is of brown leather, with a red heel, and a red rose for a tie above the instep. Fig. 12 is altogether red, in a pattern of different strengths of tint; the tie and heels being deepest in color.

Her majesty’s grand bal costumé, given during the past year, revived for a night the fashion of a century ago: and the author of these pages, was then under the necessity of hunting up the few re{54}maining makers of wooden heels, in order to furnish the correct shoe, to complete the costume of many of the most distinguished individuals, who figured on that occasion.

The making of the high-heeled shoe, was at all times a matter of great judgment and nicety of operation; the position required to be given to the heel, the aptitude of the eye and hand, necessary to the cutting down of the wood; the sewing in of the cover, kid, stuff, silk, or satin, as it might be: the getting in and securing the wood or “block;” the bracing the cover round the block; and the beautifully defined stitching, which went from corner to corner, all round the heel part, demanding altogether the cleverness of first-rate ability.

The shoes became lower in the quarters during the reign of George III., and the heel was made less clumsy. As fashion varied, larger or smaller buckles were used, and the heel was thrust further beneath the foot until about 1780, when the shoe took the form here delineated, and which is copied from Mr. Fairholt’s notes in the “Art Union,” already alluded to.{55}

From the same source, we borrow the following notices by the same writer: “About 1790, a change in the fashion of ladies’ shoes occurred. They were made very flat and low in the heel, in reality more like a slipper than a shoe. This engraving, copied from a real specimen, will show the peculiarity of its make: the low quarters, the diminutive heel, and the plaited riband and small tie in front, in place of the buckle which began to be occasionally discontinued. The duchess of York, at this time, was remarkable for the smallness of her foot, and a colored print of ‘the exact size of the duchess’ shoe,’ was published by Fores, in 1791. It measures five and three quarters inches in length; the breadth of the sole being only one and three quarters inches. It is made of green silk, ornamented with gold stars; is bound with scarlet silk; the heel is scarlet, and the shape is similar to the one engraved above, except that the heel is exactly in the modern style.” Models of this fairy shoe were made of china, as ornaments for the chimney, or drawing-room table, with cupids hovering around it.

Shoes of the old fashion, with high heels and{56} buckles, appear in prints of the early part of 1800; but buckles became unfashionable, and shoe-strings eventually triumphed, although less costly and elegant in their construction. The prince of Wales was petitioned by the alarmed buckle-makers, to discard his new-fashioned strings, and take again to buckles, by way of bolstering up their trade; but the fate of these articles was sealed, and the prince’s good-natured compliance with their wishes, did little to prevent their downfall. The buckles worn at the end of 1700, were generally exceedingly small, and so continued until they were finally disused.

Early in the reign of George III., the close fitting gentleman’s boot became general; the material used for the leg was termed grain-leather, the flesh side being left brown, and the grain blackened, and kept to the sight. In currying this sort of leather for the boot-leg, it went, in the lower part, through an ingenious process of contraction, to give it life; so that the heel of the wearer might go into it and come out again the easier; the boot, at the same time, when on, catching snugly round the small of the leg, in a sort of stocking fit.

After this appeared the “Hessian,” a boot worn over the tight-fitting pantaloon, the up{57}peaking front bearing a silk tassel. This boot was introduced from Germany, about 1789, and sometimes was called the Austrian boot. Rees, in his “Art and Mystery of the Cordwainer,” published in 1813, says, “The form at first was odious, as the close boot was then in wear, but like many fashions, at first frightful, it was then pitied, and at last adopted.”

The top-boot was worn early in the reign of George III., and took the fulness of the Hessian in its lower part, and on the introduction of the “Wellington,” the same fulness was retained.

To describe the last-named boot were useless, it has become, par excellence, the common boot, and is perhaps as universally known as the fame of the distinguished hero Wellington.{58}

UPON critically examining the various forms assumed by the coverings for the feet adopted by the nations around us, we shall find that they were in no small degree modified by the circumstances with which they were surrounded, or the necessities of the climate they inhabited.

Thus the northern nations enswathed their legs in skins, and used the same material for the shoes, binding the whole in warm folds about the leg, the thongs being fastened to them in the manner represented in plate IV., fig. 1, and which is copied from a full length figure of a Russian boor, in 1768. The sandal of a Russian lady of the same period, is given in the same plate, fig. 2, and the men of Friesland at the same time, wore sandals or shoes of a similar construction, the common people generally wearing a close leathern shoe and clog, something like those in use in the

middle ages, one delineated in fig. 3 of our plate, and is represented on the feet of a countrywoman, in the curious series of costumes of Finland, engraved in “Jeffery’s Collection of the Dresses of different Nations,” published in 1757, and which were copied from some very rare prints, at least a century earlier in point of date. Another female’s shoe is given in fig. 4; it is a low slipper-like shoe, and is secured by a band across the instep, having an ornamental clasp, like a brooch, to secure it on each side of the foot; it was probably a coarsely-made piece of jewelry, with glass or cheap stones set around it; as the people of this country at that time were fond of such showy decorations, and particularly upon their shoes. The noblemen and ladies always decorated theirs with ornaments and jewels all over the upper surface, of which we give two specimens in figs. 5 and 6: the former upon the foot of a nobleman, the latter upon that of a matron of the upper classes. It will be seen, that both are very elegant, and must have been very showy wear.

The boots of an Hungarian gentleman, in 1700, may be seen in fig. 7, of plate IV., and such boots were common to Bohemia at the same period. They are chiefly remarkable for the way in which they are cut upward from the middle{60} of the thigh to the knee, and then curl over in front of the leg.

A Tartarian lady of 1577, is exhibited by John Wiegel, the engraver of Nuremburgh, in his work on dress, in the boots delineated in fig. 8. They are remarkable for the sole to which they are affixed, and which was, no doubt, formed of some strong substance, probably with metallic hooks to assist the wearer in walking a mountainous country where frosts abound.

Descending toward the south, we shall find a lighter sort of shoe in use, and one partaking more of the character of a slipper, used more as a protection for the sole of the foot in walking, than as an article of warmth. Thus the shoes generally used in the East, scarcely do more than cover the toes, yet, from constant use, the natives hardly ever allow them to slip from the feet. The learned author of the notes to “Knight’s Pictorial Bible,” speaking from personal observation of these articles, says, “The common shoe in Turkey or Arabia, is like our slipper with quarters, except that it has a sharp and prolonged toe turned up.” No shoes in western Asia have ears, and they are generally of colored leather—red or yellow morocco in Turkey and Arabia, and green shagreen in Persia. In the latter country, the shoe or slipper in general{61} use (having no quarters), has a very high heel; but with this exception, the heels in these countries are generally flat. No shoes or even boots have more than a single sole (like what we call “pumps”), which in wet weather imbibes the water freely. When the shoe without quarters is used, a slipper, with quarters, but without a sole, is worn inside, and the outer one alone is thrown off on entering a house. But in Persia, instead of this inner shoe of leather, they use a worsted sock. Those shoes that have quarters are usually worn without any inner covering for the foot. The peasantry and the nomade tribes usually go barefoot, or wear a rude sandal or shoe of their own manufacture; those who possess a pair of red leather or other shoes, seldom wear them except on holyday occasions, so that they last a long time, if not so long as among the Maltese, with whom a pair of shoes endures for several generations, being, even on holyday occasions, more frequently carried in the hand than worn on the feet. The boots are generally of the same construction and material as the shoes; and the general form may be compared to that of the buskin, the height varying from the mid-leg to near the knee. They are of capacious breadth, except among the Persians whose boots generally fit close to the leg, and are mostly of a{62} sort of Russia leather, uncolored; whereas those of other people are, like the slipper, of red and yellow morocco. There is also a boot or shoe for walking in frosty weather, which differs from the common one only in having under the heel iron tips, which, being partly bent vertically with a jagged edge, give a hold on the ice, which prevents slipping, and are particularly useful in ascending or descending the frozen mountain paths—reminding us of the sort of boot worn by Tartarian ladies, as given in fig. 8. The shoes of the oriental ladies are sometimes highly ornamented; the covering part being wrought with gold, silver, and silk, and perhaps set with jewels, real or imitated. Examples of such decorated shoes are given in plate IV., figs. 9 and 10, and will sufficiently explain themselves to the eye of the reader, rendering detailed description unnecessary. The shoes of noblemen are of precisely similar construction.

In China, the boots and shoes of the men are worn as clumsy and inelegant as in any country.{63} They are broad at the toe, and sometimes upturned. We give a specimen of both in the foregoing engraving. They are no doubt easy to wear.

Not so are the ladies’ shoes, for they only are allowed the privilege of discomfort, fashion having in this country declared in favor of small feet, and the prejudice of the people having gone with it, the feet of all ladies of decent rank in society, are cramped in early life, by being placed in so strait a confinement, that their growth is retarded, and they are not more than three or four inches in length, from the toe to the heel. By the smallness of the foot the rank or high-breeding of the lady is decided on, and the utmost torment is endured by the girls in early life, to insure themselves this distinction in rank; the lower classes of females not being allowed to torture themselves in the same manner. The Chinese poets frequently indulge in panegyrics on the beauty of these crippled members of the body, and none of their heroines are considered perfect without excessively small feet, when they are affectionately termed by them “the little golden lilies.” It is needless to say that the tortures of early youth are succeeded by a crippled maturity, a Chinese lady of high birth being scarcely able to walk without assistance. A specimen of such a foot and shoe is given in plate III.,{64} fig. 11. These shoes are generally made of silk and embroidered in the most beautiful manner, with flowers and ornaments, in colored silk and threads of gold and silver. A piece of stout silk is generally attached to the heel for the convenience of pulling up the shoe.

Having bestowed some attention on ancient Egypt, we may briefly allude to the shoes of modern times, as given in Lane’s work devoted to the history of the manners and customs of the modern Egyptians. They, like the Persian ones, have an upturned toe, and may with equal ease be drawn on and thrown off. Yet a shoe is also worn with a high instep and high in the heel, which will be best understood by the first figure in the accompanying cut.

The Turkish ladies of the sixteenth century, and very probably much earlier, wore a very high shoe known in Europe by the name of a “chopine.” In the voyages and travels of N. de Nicholay Dauphinoys, Seigneur D’Arfreville, valet de chambre and geographer to the king of France, printed at Lyons, 1568, one of the ladies of the grand seign{65}eur’s seraglio, is represented in a pair of chopines, of which we copy one in plate III., fig. 12. This fashion spread in Europe in the early part of the seventeenth century, and it is alluded to by Hamlet, in act ii., scene 2, when he exclaims, “Your ladyship is nearer heaven than when I saw you last, by the altitude of a chopine,” by which it appears that something of the kind was known in England, where it may have been introduced from Venice, as the ladies there wore them of the most exaggerated size. Coryat, in his “Crudities,” 1611, says; “There is one thing used of the Venetian women, and some others dwelling in the cities and towns subject to signiory of Venice, that is not to be observed (I think) among any other women in Christendom”—the reader must remember that it was new to Coryat, but a common fashion in the East—“which is so common in Venice that no woman whatsoever goeth without it, either in her house or abroad—a thing made of wood and covered with leather of sundry colors; some with white, some red, some yellow. It is called a chapiney, which they never wear under their shoes. Many of these are curious painted; some of them I have also seen fairly gilt; so uncomely a thing, in my opinion, that it is a pity this foolish custom is not clean banished and exterminated out of the city. There{66}

are many of these chapineys of a great height even half a yard high, which maketh many of their women, that are very short, seem much taller than the tallest women we have in England. Also, I have heard it observed among them, that by how much the nobler a woman is, by so much the higher are her chapineys. All their gentlewomen, and most of their wives and widows that are of any wealth, are assisted and supported either by men or women, when they walk abroad, to the end they might not fall. They are borne up most commonly by the left arm; otherwise they might quickly take a fall.” In Douce’s Illustrations of Shakspere, a woodcut of such a chapiney, or chopine, is given, which is here copied; and it is an excellent ex{67}ample of the thing, showing the decoration which was at times bestowed on it.

Douce quotes some curious particulars of this fashion, in “Raymond’s Voyage through Italy,” 1648, and the following curious account of the chopine occurs: “This place [Venice] is much frequented by the walking may-poles: I mean the women. They wear their coats half too long for their bodies, being mounted on their chippeens (which are as high as a man’s leg); they walke betweene two handmaids, majestically deliberating of every step they take.” Howel also says of the Venetian women: “They are low and of small stature for the most part, which makes them to raise their bodies upon high shoes, called chapins, which gave me occasion to say that the Venetian ladies were made of three things, one part of them was wood, meaning their chapins, another part was their apparel, and the third part was a woman. The senate hath often endeavored to take away the wearing of those high shoes, but all women are so passionately delighted with this kind of state, that no law can wean them from it.” Douce adds, that “some have supposed that the jealousy of Italian husbands gave rise to the invention of the chopine;” and quotes a story from a French author, to show their dislike to an alteration; he also says,{68} that “the first ladies who rejected the use of the chopine, were the daughters of the doge Dominico Contareno, about the year 1670.” The chopine, or some kind of high shoe, was occasionally used in England. Bulwer, in his “Artificial Changeling,” p. 550, complains of this fashion as a monstrous affectation, and says that his countrywomen therein imitated the Venetian and Persian ladies. In “Sandy’s Travels,” 1615, there is a figure of a Turkish lady with chopines, and it is not improbable that the Venetians might have borrowed them from the Greek islands in the Archipelago. We know that something similar was in use among the ancient Greeks. Xenophon, in Œconomics, mentions the wife of Ischomachus as wearing high shoes, for increasing her stature. They are still worn by the women in many parts of Turkey, but more particularly at Aleppo. Douce’s notice of their antiquity, is curiously corroborated by the discovery in the tombs of ancient Egypt of such shoes. They are formed of a stout sole of wood, to which is affixed four round props, raising the wearer a foot in height; specimens were among the collections of Mr. Salt, the British consul in Egypt, from which some of the choicest Egyptian antiquities in the national collection were obtained. The other remark of Douce’s, that they{69} were probably derived from the Greek islands of the Archipelago, is confirmed by the fact that high-soled boots and shoes were much coveted by the ladies there, to raise their stature, and were worn when chopines had long been disused; thus the high-soled boots delineated in plate IV., fig. 13, are found upon the feet of “a young lady of Argentiera,” one of these islands, in a print dated 1700; and, in another of the same date, giving the costume of a lady of the neighboring island of Naxos, the shoe shown in fig. 14, is worn.

Of the modern European nations with whom we have been most in contact—Spain, France, and the Netherlands—their boots and shoes have so nearly resembled our own, as to render a detailed description scarcely necessary. Indeed, as France has been tacitly submitted to as the arbiter elegantiarum in all matters of dress, much has been derived thence.

There was, however, a French shoe that we do not ever appear to have adopted; it was made low in the quarters and ended at the instep; there was no covering for the heel, or the sides of the foot beyond it. The fashion spread to Venice, and the figure of a Venetian lady of 1750, has supplied us with the specimen in plate IV., fig. 15.

The sabots of France, is another peculiarity{70} which we never adopted, and which our peasantry have always looked on with great distaste; and it became popularly said of William III., that he had saved us from popery, slavery, and wooden shoes. They are generally clumsy enough; their large size, and bad fit, are generally improved by the introduction of others made of list, which give warmth and steadiness to the foot. A small wooden shoe is, however, made in Normandy, and else where, much like that which came into fashion about 1790, with an imitation of its fringes and pointed toe, and which is generally painted black; the ordinary sabot being totally unadorned, and the color of the wood. In the cut here given, both are introduced. Fig. 1, is the ordinary shoe; fig. 2, the extraordinary or genteel one.

And now, having in the pursuit of our history of boots and shoes,