This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 4

Author: Various

Release Date: March 12, 2005 [eBook #15345]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GREAT EVENTS BY FAMOUS HISTORIANS, VOLUME 4***

A COMPREHENSIVE AND READABLE ACCOUNT OF THE WORLD'S HISTORY, EMPHASIZING THE MORE IMPORTANT EVENTS, AND PRESENTING THESE AS COMPLETE NARRATIVES IN THE MASTER-WORDS OF THE MOST EMINENT HISTORIANS

| NON-SECTARIAN | NON-PARTISAN | NON-SECTIONAL |

ON THE PLAN EVOLVED FROM A CONSENSUS OF OPINIONS GATHERED FROM THE MOST DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARS OF AMERICA AND EUROPE, INCLUDING BRIEF INTRODUCTIONS BY SPECIALISTS TO CONNECT AND EXPLAIN THE CELEBRATED NARRATIVES. ARRANGED CHRONOLOGICALLY. WITH THOROUGH INDICES, BIBLIOGRAPHIES, CHRONOLOGIES, AND COURSES OF READING

Our modern civilization is built up on three great corner-stones, three inestimably valuable heritages from the past. The Græco-Roman civilization gave us our arts and our philosophies, the bases of intellectual power. The Hebrews bequeathed to us the religious idea, which has saved man from despair, has been the potent stimulus to two thousand years of endurance and hope. The Teutons gave us a healthy, sturdy, uncontaminated physique, honest bodies and clean minds, the lack of which had made further progress impossible to the ancient world.

This last is what made necessary the barbarian overthrow of Rome, if the world was still to advance. The slowly progressing knowledge of the arts and handicrafts which we have seen passed down from Egypt to Babylonia, to Persia, Greece, and Rome, had not been acquired without heavy loss. The system of slavery which allowed the few to think, while the many were constrained to toil as beasts, had eaten like a canker into the heart of society. The Roman world was repeating the oft-told tale of the past, and sinking into the lifeless formalism of which Egypt was the type. Man had become wise, but worthless.

As though on purpose to prove to future generations how utterly worthless, the Roman civilization was allowed to continue uninterrupted in one unneeded corner of its former domains. For over a thousand years the successors of Theodosius and of Constantine held unbroken sway in the capital which the latter had founded. They only succeeded in emphasizing how futile their culture had become.

The entire ten centuries that followed the overthrow of Rome have long been spoken of as the "Dark Ages," but, considering how infinitely darker those same ages must have become without the intervention of the Teutons, present criticism begins to protest against the term. All that was lost with the ancient world was something of intellectual keenness, something of artistic culture, quickly regained when man was once more ripe for them. What the Teutons had to offer of infinitely greater worth, what they had developed in their cold, northern forests, was their sense of liberty and equality, their love of honesty, their respect for womankind. It is not too much to say that, without these, any higher progress was, and always will be, impossible.

In short, the Roman and Grecian races had become impotent and decrepit. The high destiny of man lay not with them, but with the younger race, for whom all earlier civilizations had but prepared the way.

Who were these Teutons? Rome knew them only vaguely as wild tribes dwelling in the gloom of the great forest wilderness. In reality they were but the vanguard of vast races of human beings who through ages had been slowly populating all Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. Beyond the Teutons were other Aryans, the Slavs. Beyond these were vague non-Aryan races like the Huns, content to direct their careers of slaughter against one another, and only occasionally and for a moment flaring with red-fire beacons of ruin along the edge of the Aryan world.

Some at least of the Teutonic tribes had grown partly civilized. The Germans along the Rhine, and the Goths along the Danube, had been from the time of Augustus in more or less close contact with Rome. Germanicus had once subdued almost the whole of Germany; later emperors had held temporarily the broad province of Dacia, beyond the Danube. The barbarians were eagerly enlisted in the Roman army. During the closing centuries of decadence they became its main support; they rose to high commands; there were even barbarian emperors at last. The intermingling of the two worlds thus became extensive, and the Teutons learned much of Rome. The Goths whom Theodosius permitted to settle within its dominions were already partly Christian.

THE PERIOD OF INVASION

It was these same Goths who became the immediate cause of Rome's downfall. Theodosius had kept them in restraint; his feeble sons scarce even attempted it. The intruders found a famous leader in Alaric, and, after plundering most of the Grecian peninsula, they ravaged Italy, ending in 410 with the sack of Rome itself.[1]

This seems to us, perhaps, a greater event than it did to its own generation. The "Emperor of the West," the degenerate son of Theodosius, was not within the city when it fell; and the story is told that, on hearing the news, he expressed relief, because he had at first understood that the evil tidings referred to the death of a favorite hen named Rome. The tale emphasizes the disgrace of the famous capital; it had sunk to be but one city among many. Alaric's Goths had been nominally an army belonging to the Emperor of the East; their invasion was regarded as only one more civil war.

Besides, the Roman world might yet have proved itself big enough to assimilate and engulf the entire mass of this already half-civilized people. Its name was still a spell on them. Ataulf, the successor of Alaric, was proud to accept a Roman title and become a defender of the Empire. He marched his followers into Gaul under a commission to chastise the "barbarians" who were desolating it.

These later comers were the instruments of that more overwhelming destruction for which the Goths had but prepared the way. To resist Alaric, the Roman legions had been withdrawn from all the western frontiers, and thus more distant and far more savage tribes of the Teutons beheld the glittering empire unprotected, its pathways most alluringly left open. They began streaming across the undefended Rhine and Danube. Their bands were often small and feeble, such as earlier emperors would have turned back with ease; but now all this fascinating world of wealth, so dimly known and doubtless fiercely coveted, lay helpless, open to their plundering. The Vandals ravaged Gaul and Spain, and, being defeated by the Goths, passed on into Africa. The Saxons and Angles penetrated England[2] and fought there for centuries against the desperate Britons, whom the Roman legions had perforce abandoned to their fate. The Franks and Burgundians plundered Gaul.

Fortunately the invading tribes were on the whole a kindly race. When they joyously whirled their huge battle-axes against iron helmets, smashing down through bone and brain beneath, their delight was not in the scream of the unlucky wretch within, but in their own vigorous sweep of muscle, in the conscious power of the blow. Fierce they were, but not coldly cruel like the ancients. The condition of the lower classes certainly became no worse for their invasion; it probably improved. Much the new-comers undoubtedly destroyed in pure wantonness. But there was much more that they admired, half understood, and sought to save.

Behind them, however, came a conqueror of far more terrible mood. We have seen that when the Goths first entered Roman territory they were driven on by a vast migration of the Asiatic Huns. These wild and hideous tribes then spent half a century roaming through central Europe, ere they were gathered into one huge body by their great chief, Attila, and in their turn approached the shattered regions of the Mediterranean.[3] Their invasion, if we are to trust the tales of their enemies, from whom alone we know of them, was incalculably more destructive than all those of the Teutons combined. The Huns delighted in suffering; they slew for the sake of slaughter. Where they passed they left naught but an empty desert, burned and blackened and devoid of life.

Crossing the Danube, they ravaged the Roman Empire of the East almost without opposition. Only the impregnable walls of Constantinople resisted the destruction. A few years later the savage horde appeared upon the Rhine, and in enormous numbers penetrated Gaul. No people had yet understood them, none had even checked their career. The white races seemed helpless against this "yellow peril," this "Scourge of God," as Attila was called.

Goths and Romans and all the varied tribes which were ranging in perturbed whirl through unhappy Gaul laid aside their lesser enmities and met in common cause against this terrible invader. The battle of Châlons, 451,[4] was the most tremendous struggle in which Turanian was ever matched against Aryan, the one huge bid of the stagnant, unprogressive races, for earth's mastery.

Old chronicles rise into poetry at thought of that immeasurable battle. They figure the slain by hundred thousands; they describe the souls of the dead as rising above the bodies and continuing their furious struggle in the air. Attila was checked and drew back. Defeated we can scarce call him, for only a year or so later we find him ravaging Italy. Fugitives fleeing before him to the marshes lay the first stones of Venice.[5] Leo, the great Pope, pleads with him for Rome. His forces, however, are obviously weaker than they were. He retreats; and after his death his irresponsible followers disappear forever in the wilderness.

THE PERIOD OF SETTLEMENT

Toward the close of this tumultuous fifth century, the various Teutonic tribes show distinct tendencies toward settling down and forming kingdoms amid the various lands they have overrun. The Vandals build a state in Africa, and from the old site of Carthage send their ships to the second sack of Rome. The Visigoths form a Spanish kingdom, which lasts over two hundred years. The Ostrogoths construct an empire in Italy (493-554), and, under the wise rule of their chieftain Theodoric, men joyfully proclaim that peace and happiness and prosperity have returned to earth. Most important of all in its bearing upon later history, the Franks under Clovis begin the building of France.[6]

Encouraged by these milder days, the Roman emperors of Constantinople attempt to reclaim their old domain. The reign of Justinian begins (527-565), and his great general Belisarius temporarily wins back for him both Africa and Italy. This was a comparatively unimportant detail, a mere momentary reversal of the historic tide. Justinian did for the future a far more noted service.

If there was one subject which Roman officials had learned thoroughly through their many generations of rule, it was the set of principles by which judges must be guided in their endeavor to do justice. Long practical experience of administration made the Romans the great law-givers of antiquity. And now Justinian set his lawyers to work to gather into a single code, or "digest," all the scattered and elaborate rules and decisions which had place in their gigantic system.[7]

It is this Code of Justinian which, handed down through the ages, stands as the basis of much of our law to-day. It shapes our social world, it governs the fundamental relations between man and man. There are not wanting those who believe its principles are wrong, who aver that man's true attitude toward his fellows should be wholly different from its present artificial pose. But whether for better or for worse we live to-day by Roman law.

This law the Teutons were slowly absorbing. They accepted the general structure of the world into which they had thrust themselves; they continued its style of building and many of its rougher arts; they even adopted its language, though in such confused and awkward fashion that Italy, France, and Spain grew each to have a dialect of its own. And most important of all, they accepted the religion, the Christian religion of Rome. Missionaries venture forth again. Augustine preaches in England.[8] Boniface penetrates the German wilds.

It must not be supposed that the moment a Teuton accepted baptism he became filled with a pure Christian spirit of meekness and of love. On the contrary, he probably remained much the same drunken, roistering heathen as before. But he was brought in contact with noble examples in the lives of some of the Christian bishops around him; great truths began to touch his mobile nature; he was impressed, softened; he began to think and feel.

Given a couple of centuries of this, we really begin to see some very encouraging results. We realize that for once we are being allowed to study a civilization in its earlier stages, to be present almost at its birth, to watch the methods of the Master-builder in the making of a race. Gazing at similar developments in the days of Egypt and Babylon, we guessed vaguely that they must have been of slowest growth. Here at last one takes place under our eyes, and it does not need so many ages after all. There is no study more fascinating than to trace the slow changes stamping themselves ineradicably upon the Teutonic mind and soul during these misty far-off centuries of turmoil.

On the whole, of course, the sixth, seventh, and even the eighth centuries form a period of strife. The Teutons had spent too many ages warring against one another in petty strife to abandon the pleasure in a single generation. Men fought because they liked fighting, much as they play football to-day. Then, too, there came another great outburst of Semite religious enthusiasm. Mahomet[9] started the Arabs on their remarkable career of conquest.

THE MAHOMETAN OUTBURST

Mahomet himself died (632) before he had fully established his influence even over Arabia: his successors had practically to reconquer it. Yet within five years of his death the Arabs had mastered Syria.[10] They spread like some sudden, unexpected, immeasurable whirlwind. Ancient Persia went down before them. By 640 they had trampled Egypt under foot, and destroyed the celebrated Alexandrian library.[11] They swept over all Africa, completely obliterating every trace of Vandal or of Roman. Their dominion reached farther east than that of Alexander. They wrested most of its Asiatic possessions from the pretentious Empire at Constantinople, and reduced that exhausted State to a condition of weakness from which it never arose. Then, passing on through their African possessions, they entered Spain and overthrew the kingdom of the Visigoths.[12] It was a storm whose end no man could measure, whose coming none could have foreseen. And then, just a century after Mahomet's death, the Arabs, pressing on through Spain, encountered the Franks on the plains of France.

A thousand years had passed since Semitic Carthage had fallen before Aryan Rome. Now once again the Semites, far more dangerous because in the full tide of the religious frenzy of their race, threatened to engulf the Aryan world. They were repulsed by the still sturdy Franks under their great leader, Charles Martel, at Tours. The battle of Tours[13] was only less momentous to the human race than that of Châlons. What the Arab domination of Europe would have meant we can partly guess by looking at the lax and lawless states of Northern Africa to-day. These fair lands, under both Roman and Vandal, had long been sharing the lot of Aryan Europe; they seemed destined to follow in its growth and fortune. But the Arab conquest restored them to Semitism, made Asia the seat from which they were to have their training, attached them to the chariot of sloth instead of that of effort. What they are to-day, all Europe might have been.

Yet with the picture of these fifth and sixth and seventh centuries of battle full before us, we are not tempted to glory overmuch even in such victories as Tours and Châlons. We see war for what it has ever been—the curse of man, the hugest hinderance to our civilization. While men fight they have small time for thought or art or any soft or kindly sentiment. The survivors may with good luck develop into a stronger breed; they are inevitably more brutal.

We thus begin to recognize just how necessary for human progress was the work Rome had been engaged in. By holding the world at peace, she had given humankind at least the opportunity to grow. The moment her restraining hand was shaken off, war sprang up everywhere. Not only do we find the inheritors of her territory fighting among themselves, they are exposed to the savagery of Attila, the fury of the Arabs. New bands of more distant Teutons come, ever pushing in amid their half-settled brethren, overthrowing them in turn. The Lombards capture Northern Italy, only Venice remaining safe amid her marshes.[14] The East-Franks—that is, the semi-barbarians still remaining in the wilderness—master the more cultured West-Franks, who hold Gaul. No sooner does civilization start up than it is trodden on.

THE EMPIRE OF CHARLEMAGNE

At length there arose among the Franks a series of stalwart rulers, keen-eyed, penetrating somewhat at least into the meaning of their world, determined to have peace if they must fight for it. Charles Martel was one of these. Then came his son Pépin,[15] who held out his hand to the bishops of Rome, acknowledged their vast civilizing influence, saved them from the Lombards, and joined church and state once more in harmony. After Pépin came his son, Charlemagne, whose reign marks an epoch of the world. The peace his fathers had striven for, he won at last, though only, as they had done, by constant fighting. He attacked the Arabs and reduced them to permanent feebleness in Spain. He turned backward the Teutonic movement, marching his Franks into the German forests, and in campaign after campaign defeating the wild tribes that still remained there. The strongest of them, the Saxons, accepted an enforced Christianity. Even the vague races beyond the German borders were so harried, so weakened, that they ceased to be a serious menace.

Charlemagne[16] had thus in very truth created a new empire. He had established at least one central spot, so hedged round by border dependencies that no later wave of barbarians ever quite succeeded in submerging it. The bones of the great Emperor, in their cathedral sepulchre at Aix, have never been disturbed by an unfriendly hand, Paris submitted to no new conquest until over a thousand years later, when the nineteenth century had stolen the barbarity from war. It was then no more than a just acknowledgment of Charlemagne's work when, on Christmas Day of the year 800, as he rose from kneeling at the cathedral altar in Rome, he was crowned by the Pope whom he had defended, and hailed by an enthusiastic people as lord of a re-created "Holy Roman Empire."

In England, also, the centuries of warfare among the Britons and the various antagonistic Teutonic tribes seemed drawing to an end. Egbert established the "heptarchy";[17] that is, became overlord of all the lesser kings. Truly for a moment civilization seemed reëstablished. The arts returned to prominence. England could send so noteworthy a scholar as Alcuin to the aid of the great Emperor. Charlemagne encouraged learning; Alcuin established schools. Once more men sowed and reaped in security. The "Roman peace" seemed come again.

[FOR THE NEXT SECTION OF THIS GENERAL SURVEY SEE VOLUME V.]

[5] See Foundation of Venice.

[9] See The Hegira.

[12] See Saracens in Spain.

[13] See Battle of Tours.

Of the two great historical divisions of the Gothic race the Visigoths or West Goths were admitted into the Roman Empire in A.D. 376, when they sought protection from the pursuing Huns, and were transported across the Danube to the Moesian shore. The story of their gradual progress in civilization and growth in military power, which at last enabled them to descend with overwhelming force upon Rome itself, forms one of the romances of history.

From their first reception into Lower Moesia the Visigoths were subjected to the most contemptuous and oppressive treatment by the Romans who had admitted them into their domains. At last the outraged colonists were provoked to revolt, and a stubborn war ensued, which was ended at Adrianople, August 9, A.D. 378, by the defeat of the emperor Valens and the destruction of his army, two-thirds of his soldiers perishing with Valens himself, whose body was never found.

In 382 a treaty was made which restored peace to the Eastern Empire, the Visigoths nominally owning the sovereignty of Rome, but living in virtual independence. They continued to increase in numbers and in power, and in A.D. 395, under Alaric, their King, they invaded Greece, but were compelled by Stilicho, in 397, to retire into Epirus. Stilicho was the commander-in-chief of the Roman army, and the guardian of the young emperor Honorius. Alaric soon afterward became commander-in-chief of the Roman forces in Eastern Illyricum and held that office for four years. During that time he remained quiet, arming and drilling his followers, and waiting for the opportunity to make a bold stroke for a wider and more secure dominion.

In the autumn of A.D. 400, while Stilicho was campaigning in Gaul, Alaric made his first invasion of Italy, and for more than a year he ranged at will over the northern part of the peninsula. Rome was made ready for defence, and Honorius, the weak Emperor of the Western Empire, prepared for flight into Gaul; but on March 19th of the year 402, Stilicho surprised the camp of Alaric, near Pollentia, while most of his followers were at worship, and after a desperate battle they were beaten. Alaric made a safe retreat, and soon afterward crossed the Po, intending to march against Rome, but desertions from his ranks caused him to abandon that purpose. In 403 he was overtaken and again defeated by Stilicho at Verona, Alaric himself barely escaping capture. Stilicho, however, permitted him—some historians say, bribed him—to withdraw to Illyricum, and he was made prefect of Western Illyricum by Honorius. Such is the prelude, followed in history by the amazing exploits of Alaric's second invasion of Italy.

His troops having revolted at Pavia, Stilicho fled to Ravenna, where the ungrateful Emperor had him put to death August 23, 408. In October of that year Alaric crossed the Alps, advancing without resistance until he reached Ravenna; after threatening Ravenna he marched upon Rome and began the preparations that ended in the sack of the city.

The incapacity of a weak and distracted government may often assume the appearance, and produce the effects, of a treasonable correspondence with the public enemy. If Alaric himself had been introduced into the council of Ravenna, he would probably have advised the same measures which were actually pursued by the ministers of Honorius. The King of the Goths would have conspired, perhaps with some reluctance, to destroy the formidable adversary, by whose arms, in Italy as well as in Greece, he had been twice overthrown. Their active and interested hatred laboriously accomplished the disgrace and ruin of the great Stilicho. The valor of Sarus, his fame in arms, and his personal, or hereditary, influence over the confederate Barbarians, could recommend him only to the friends of their country, who despised, or detested, the worthless characters of Turpilio, Varanes, and Vigilantius. By the pressing instances of the new favorites, these generals, unworthy as they had shown themselves of the names of soldiers, were promoted to the command of the cavalry, of the infantry, and of the domestic troops. The Gothic prince would have subscribed with pleasure the edict which the fanaticism of Olympius dictated to the simple and devout Emperor.

Honorius excluded all persons who were adverse to the Catholic Church from holding any office in the State; obstinately rejected the service of all those who dissented from his religion; and rashly disqualified many of his bravest and most skilful officers who adhered to the pagan worship or who had imbibed the opinions of Arianism. These measures, so advantageous to an enemy, Alaric would have approved, and might perhaps have suggested; but it may seem doubtful whether the Barbarian would have promoted his interest at the expense of the inhuman and absurd cruelty which was perpetrated by the direction, or at least with the connivance, of the imperial ministers. The foreign auxiliaries who had been attached to the person of Stilicho lamented his death; but the desire of revenge was checked by a natural apprehension for the safety of their wives and children, who were detained as hostages in the strong cities of Italy, where they had likewise deposited their most valuable effects.

At the same hour, and as if by a common signal, the cities of Italy were polluted by the same horrid scenes of universal massacre and pillage which involved in promiscuous destruction the families and fortunes of the Barbarians. Exasperated by such an injury, which might have awakened the tamest and most servile spirit, they cast a look of indignation and hope toward the camp of Alaric, and unanimously swore to pursue, with just and implacable war, the perfidious nation that had so basely violated the laws of hospitality. By the imprudent conduct of the ministers of Honorius the republic lost the assistance, and deserved the enmity, of thirty thousand of her bravest soldiers; and the weight of that formidable army, which alone might have determined the event of the war, was transferred from the scale of the Romans into that of the Goths.

In the arts of negotiation, as well as in those of war, the Gothic King maintained his superior ascendant over an enemy, whose seeming changes proceeded from the total want of counsel and design. From his camp, on the confines of Italy, Alaric attentively observed the revolutions of the palace, watched the progress of faction and discontent, disguised the hostile aspect of a Barbarian invader, and assumed the more popular appearance of the friend and ally of the great Stilicho; to whose virtues, when they were no longer formidable, he could pay a just tribute of sincere praise and regret.

The pressing invitation of the malcontents, who urged the King of the Goths to invade Italy, was enforced by a lively sense of his personal injuries; and he might speciously complain that the Imperial ministers still delayed and eluded the payment of the four thousand pounds of gold which had been granted by the Roman senate, either to reward his services or to appease his fury. His decent firmness was supported by an artful moderation, which contributed to the success of his designs. He required a fair and reasonable satisfaction; but he gave the strongest assurances that, as soon as he had obtained it, he would immediately retire. He refused to trust the faith of the Romans, unless Aetius and Jason, the sons of two great officers of state, were sent as hostages to his camp; but he offered to deliver, in exchange, several of the noblest youths of the Gothic nation. The modesty of Alaric was interpreted, by the ministers of Ravenna, as a sure evidence of his weakness and fear. They disdained either to negotiate a treaty or to assemble an army; and with a rash confidence, derived only from their ignorance of the extreme danger, irretrievably wasted the decisive moments of peace and war. While they expected, in sullen silence, that the Barbarians should evacuate the confines of Italy, Alaric, with bold and rapid marches, passed the Alps and the Po; hastily pillaged the cities of Aquileia, Altinum, Concordia, and Cremona, which yielded to his arms; increased his forces by the accession of thirty thousand auxiliaries; and, without meeting a single enemy in the field, advanced as far as the edge of the morass which protected the impregnable residence of the Emperor of the West.

Instead of attempting the hopeless siege of Ravenna, the prudent leader of the Goths proceeded to Rimini, stretched his ravages along the sea-coast of the Adriatic, and meditated the conquest of the ancient mistress of the world. An Italian hermit, whose zeal and sanctity were respected by the Barbarians themselves, encountered the victorious monarch, and boldly denounced the indignation of heaven against the oppressors of the earth; but the saint himself was confounded by the solemn asseveration of Alaric, that he felt a secret and preternatural impulse, which directed, and even compelled, his march to the gates of Rome. He felt that his genius and his fortune were equal to the most arduous enterprises; and the enthusiasm which he communicated to the Goths insensibly removed the popular, and almost superstitious, reverence of the nations for the majesty of the Roman name. His troops, animated by the hopes of spoil, followed the course of the Flaminian way, occupied the unguarded passes of the Apennine, descended into the rich plains of Umbria; and, as they lay encamped on the banks of the Clitumnus, might wantonly slaughter and devour the milk-white oxen, which had been so long reserved for the use of Roman triumphs. A lofty situation, and a seasonable tempest of thunder and lightning, preserved the little city of Narni; but the King of the Goths, despising the ignoble prey, still advanced with unabated vigor; and after he had passed through the stately arches, adorned with the spoils of Barbaric victories, he pitched his camp under the walls of Rome.

By a skilful disposition of his numerous forces, who impatiently watched the moment of an assault, Alaric encompassed the walls, commanded the twelve principal gates, intercepted all communication with the adjacent country, and vigilantly guarded the navigation of the Tiber, from which the Romans derived the surest and most plentiful supply of provisions. The first emotions of the nobles and of the people were those of surprise and indignation that a vile Barbarian should dare to insult the capital of the world; but their arrogance was soon humbled by misfortune; and their unmanly rage, instead of being directed against an enemy in arms, was meanly exercised on a defenceless and innocent victim. Perhaps in the person of Serena, the Romans might have respected the niece of Theodosius, the aunt, nay, even the adoptive mother, of the reigning Emperor; but they abhorred the widow of Stilicho; and they listened with credulous passion to the tale of calumny, which accused her of maintaining a secret and criminal correspondence with the Gothic invader. Actuated or overawed by the same popular frenzy, the senate, without requiring any evidence of her guilt, pronounced the sentence of her death. Serena was ignominiously strangled; and the infatuated multitude were astonished to find that this cruel act of injustice did not immediately produce the retreat of the Barbarians and the deliverance of the city.

That unfortunate city gradually experienced the distress of scarcity, and at length the horrid calamities of famine. The daily allowance of three pounds of bread was reduced to one-half, to one-third, to nothing; and the price of corn still continued to rise in a rapid and extravagant proportion. The poorer citizens, who were unable to purchase the necessaries of life, solicited the precarious charity of the rich; and for a while the public misery was alleviated by the humanity of Læta, the widow of the emperor Gratian, who had fixed her residence at Rome, and consecrated to the use of the indigent the princely revenue which she annually received from the grateful successors of her husband. But these private and temporary donatives were insufficient to appease the hunger of a numerous people; and the progress of famine invaded the marble palaces of the senators themselves. The persons of both sexes, who had been educated in the enjoyment of ease and luxury, discovered how little is requisite to supply the demands of nature, and lavished their unavailing treasures of gold and silver to obtain the coarse and scanty sustenance which they would formerly have rejected with disdain. The food the most repugnant to sense or imagination, the aliments the most unwholesome and pernicious to the constitution, were eagerly devoured, and fiercely disputed, by the rage of hunger. A dark suspicion was entertained that some desperate wretches fed on the bodies of their fellow-creature, whom they had secretly murdered; and even mothers—such was the horrid conflict of the two most powerful instincts implanted by nature in the human breast—even mothers are said to have tasted the flesh of their slaughtered infants!

Many thousands of the inhabitants of Rome expired in their houses or in the streets for want of sustenance; and as the public sepulchres without the walls were in the power of the enemy, the stench which arose from so many putrid and unburied carcasses infected the air; and the miseries of famine were succeeded and aggravated by the contagion of a pestilential disease. The assurances of speedy and effectual relief, which were repeatedly transmitted from the court of Ravenna, supported for some time the fainting resolution of the Romans, till at length the despair of any human aid tempted them to accept the offers of a preternatural deliverance. Pompeianus, prefect of the city, had been persuaded, by the art or fanaticism of some Tuscan diviners, that, by the mysterious force of spells and sacrifices, they could extract the lightning from the clouds, and point those celestial fires against the camp of the Barbarians. The important secret was communicated to Innocent, the Bishop of Rome; and the successor of St. Peter is accused, perhaps with foundation, of preferring the safety of the republic to the rigid severity of the Christian worship. But when the question was agitated in the senate; when it was proposed, as an essential condition, that those sacrifices should be performed in the Capitol, by the authority, and in the presence, of the magistrates, the majority of that respectable assembly, apprehensive either of the divine or of the Imperial displeasure, refused to join in an act which appeared almost equivalent to the public restoration of paganism.

The last resource of the Romans was in the clemency, or at least in the moderation, of the King of the Goths. The senate, who in this emergency assumed the supreme powers of government, appointed two ambassadors to negotiate with the enemy. This important trust was delegated to Basilius, a senator of Spanish extraction, and already conspicuous in the administration of provinces; and to John, the first tribune of the notaries, who was peculiarly qualified by his dexterity in business, as well as by his former intimacy with the Gothic prince. When they were introduced into his presence, they declared, perhaps in a more lofty style than became their abject condition, that the Romans were resolved to maintain their dignity, either in peace or war; and that, if Alaric refused them a fair and honorable capitulation, he might sound his trumpets, and prepare to give battle to an innumerable people, exercised in arms, and animated by despair. "The thicker the hay, the easier it is mowed," was the concise reply of the Barbarian; and this rustic metaphor was accompanied by a loud and insulting laugh, expressive of his contempt for the menaces of an unwarlike populace, enervated by luxury before they were emaciated by famine. He then condescended to fix the ransom which he would accept as the price of his retreat from the walls of Rome: all the gold and silver in the city, whether it were the property of the State or of individuals; all the rich and precious movables; and all the slaves who could prove their title to the name of Barbarians. The ministers of the senate presumed to ask, in a modest and suppliant tone, "If such, O king, are your demands, what do you intend to leave us?"

"Your lives!" replied the haughty conqueror.

They trembled and retired. Yet, before they retired, a short suspension of arms was granted, which allowed some time for a more temperate negotiation. The stern features of Alaric were insensibly relaxed; he abated much of the rigor of his terms; and at length consented to raise the siege on the immediate payment of five thousand pounds of gold, of thirty thousand pounds of silver, of four thousand robes of silk, of three thousand pieces of fine scarlet cloth, and of three thousand pounds weight of pepper. But the public treasury was exhausted; the annual rents of the great estates in Italy and the provinces were intercepted by the calamities of war; the gold and gems had been exchanged, during the famine, for the vilest sustenance; the hoards of secret wealth were still concealed by the obstinacy of avarice; and some remains of consecrated spoils afforded the only resource that could avert the impending ruin of the city.

As soon as the Romans had satisfied the rapacious demands of Alaric, they were restored, in some measure, to the enjoyment of peace and plenty. Several of the gates were cautiously opened; the importation of provisions from the river and the adjacent country was no longer obstructed by the Goths; the citizens resorted in crowds to the free market, which was held during three days in the suburbs; and while the merchants who undertook this gainful trade made a considerable profit, the future subsistence of the city was secured by the ample magazines which were deposited in the public and private granaries.

A more regular discipline than could have been expected was maintained in the camp of Alaric; and the wise Barbarian justified his regard for the faith of treaties by the just severity with which he chastised a party of licentious Goths who had insulted some Roman citizens on the road to Ostia. His army, enriched by the contributions of the capital, slowly advanced into the fair and fruitful province of Tuscany, where he proposed to establish his winter quarters; and the Gothic standard became the refuge of forty thousand Barbarian slaves, who had broken their chains, and aspired, under the command of their great deliverer, to revenge the injuries and the disgrace of their cruel servitude. About the same time he received a more honorable reinforcement of Goths and Huns, whom Adolphus, the brother of his wife, had conducted, at his pressing invitation, from the banks of the Danube to those of the Tiber; and who had cut their way, with some difficulty and loss, through the superior numbers of the Imperial troops. A victorious leader, who united the daring spirit of a Barbarian with the art and discipline of a Roman general, was at the head of a hundred thousand fighting men; and Italy pronounced, with terror and respect, the formidable name of Alaric.

At the distance of fourteen centuries, we may be satisfied with relating the military exploits of the conquerors of Rome, without presuming to investigate the motives of their political conduct.

In the midst of his apparent prosperity, Alaric was conscious, perhaps, of some secret weakness, some internal defect; or perhaps the moderation which he displayed was intended only to deceive and disarm the easy credulity of the ministers of Honorius. The King of the Goths repeatedly declared that it was his desire to be considered as the friend of peace and of the Romans. Three senators, at his earnest request, were sent ambassadors to the court of Ravenna, to solicit the exchange of hostages and the conclusion of the treaty; and the proposals, which he more clearly expressed during the course of the negotiations, could only inspire a doubt of his sincerity as they might seem inadequate to the state of his fortune. The Barbarian still aspired to the rank of master-general of the armies of the West; he stipulated an annual subsidy of corn and money; and he chose the provinces of Dalmatia, Noricum, and Venetia for the seat of his new kingdom, which would have commanded the important communication between Italy and the Danube. If these modest terms should be rejected, Alaric showed a disposition to relinquish his pecuniary demands, and even to content himself with the possession of Noricum; an exhausted and impoverished country perpetually exposed to the inroads of the Barbarians of Germany.

But the hopes of peace were disappointed by the weak obstinacy, or interested views, of the minister Olympius. Without listening to the salutary remonstrances of the senate, he dismissed their ambassadors under the conduct of a military escort, too numerous for a retinue of honor and too feeble for an army of defence. Six thousand Dalmatians, the flower of the Imperial legions, were ordered to march from Ravenna to Rome, through an open country which was occupied by the formidable myriads of the Barbarians. These brave legionaries, encompassed and betrayed, fell a sacrifice to ministerial folly; their general, Valens, with a hundred soldiers, escaped from the field of battle; and one of the ambassadors, who could no longer claim the protection of the law of nations, was obliged to purchase his freedom with a ransom of thirty thousand pieces of gold. Yet Alarie, instead of resenting this act of impotent hostility, immediately renewed his proposals of peace; and the second embassy of the Roman senate, which derived weight and dignity from the presence of Innocent, bishop of the city, was guarded from the dangers of the road by a detachment of Gothic soldiers.

Olympius might have continued to insult the just resentment of a people who loudly accused him as the author of the public calamities; but his power was undermined by the secret intrigues of the palace. The favorite eunuchs transferred the government of Honorius, and the Empire, to Jovius, the prætorian prefect; an unworthy servant, who did not atone, by the merit of personal attachment, for the errors and misfortunes of his administration. The exile, or escape, of the guilty Olympius, reserved him for more vicissitudes of fortune: he experienced the adventure of an obscure and wandering life; he again rose to power; he fell a second time into disgrace; his ears were cut off; he expired under the lash; and his ignominious death afforded a grateful spectacle to the friends of Stilicho.

After the removal of Olympius, whose character was deeply tainted with religious fanaticism, the pagans and heretics were delivered from the impolitic proscription which excluded them from the dignities of the State. The brave Gennerid, a soldier of Barbarian origin, who still adhered to the worship of his ancestors, had been obliged to lay aside the military belt; and though he was repeatedly assured by the Emperor himself that laws were not made for persons of his rank or merit, he refused to accept any partial dispensation, and persevered in honorable disgrace till he had extorted a general act of justice from the distress of the Roman Government. The conduct of Gennerid, in the important station to which he was promoted or restored, of master-general of Dalmatia, Pannonia, Noricum, and Rhætia, seemed to revive the discipline and spirit of the republic. From a life of idleness and want, his troops were soon habituated to severe exercise and plentiful subsistence; and his private generosity often supplied the rewards which were denied by the avarice, or poverty, of the court of Ravenna.

The valor of Gennerid, formidable to the adjacent Barbarians, was the firmest bulwark of the Illyrian frontier; and his vigilant care assisted the Empire with a reinforcement of ten thousand Huns, who arrived on the confines of Italy, attended by such a convoy of provisions, and such a numerous train of sheep and oxen, as might have been sufficient, not only for the march of an army, but for the settlement of a colony.

But the court and councils of Honorius still remained a scene of weakness and distraction, of corruption and anarchy. Instigated by the prefect Jovius, the guards rose in furious mutiny, and demanded the heads of two generals and of the two principal eunuchs. The generals, under a perfidious promise of safety, were sent on shipboard and privately executed; while the favor of the eunuchs procured them a mild and secure exile at Milan and Constantinople. Eusebius the eunuch, and the Barbarian Allobich, succeeded to the command of the bed-chamber and of the guards; and the mutual jealousy of these subordinate ministers was the cause of their mutual destruction. By the insolent order of the count of the domestics, the great chamberlain was shamefully beaten to death with sticks, before the eyes of the astonished Emperor; and the subsequent assassination of Allobich, in the midst of a public procession, is the only circumstance of his life in which Honorius discovered the faintest symptom of courage or resentment.

Yet before they fell, Eusebius and Allobich had contributed their part to the ruin of the Empire, by opposing the conclusion of a treaty which Jovius, from a selfish, and perhaps a criminal, motive, had negotiated with Alaric, in a personal interview under the walls of Rimini. During the absence of Jovius, the Emperor was persuaded to assume a lofty tone of inflexible dignity, such as neither his situation nor his character could enable him to support; and a letter, signed with the name of Honorius, was immediately despatched to the prætorian prefect, granting him a free permission to dispose of the public money, but sternly refusing to prostitute the military honors of Rome to the proud demands of a Barbarian. This letter was imprudently communicated to Alaric himself; and the Goth, who in the whole transaction had behaved with temper and decency, expressed, in the most outrageous language, his lively sense of the insult so wantonly offered to his person and to his nation.

The conference of Rimini was hastily interrupted; and the prefect Jovius, on his return to Ravenna, was compelled to adopt, and even to encourage, the fashionable opinions of the court. By his advice and example, the principal officers of the State and army were obliged to swear that, without listening, in any circumstances, to any conditions of peace, they would still persevere in perpetual and implacable war against the enemy of the republic. This rash engagement opposed an insuperable bar to all future negotiation. The ministers of Honorius were heard to declare that if they had only invoked the name of the Deity they would consult the public safety, and trust their souls to the mercy of heaven; but they had sworn by the sacred head of the Emperor himself; they had touched, in solemn ceremony, that august seat of majesty and wisdom; and the violation of their oath would expose them, to the temporal penalties of sacrilege and rebellion.

While the Emperor and his court enjoyed, with sullen pride, the security of the marshes and fortifications of Ravenna, they abandoned Rome, almost without defence, to the resentment of Alaric. Yet such was the moderation which he still preserved, or affected, that, as he moved with his army along the Flaminian way, he successively despatched the bishops of the towns of Italy to reiterate his offers of peace and to conjure the Emperor that he would save the city and its inhabitants from hostile fire and the sword of the Barbarians. These impending calamities were, however, averted, not indeed by the wisdom of Honorius, but by the prudence or humanity of the Gothic King; who employed a milder, though not less effectual, method of conquest. Instead of assaulting the capital, he successfully directed his efforts against the port of Ostia, one of the boldest and most stupendous works of Roman magnificence.

The accidents to which the precarious subsistence of the city was continually exposed in a winter navigation and an open road, had suggested to the genius of the first Cæsar the useful design which was executed under the reign of Claudius. The artificial moles, which formed the narrow entrance, advanced far into the sea, and firmly repelled the fury of the waves, while the largest vessels securely rode at anchor within three deep and capacious basins, which received the northern branch of the Tiber, about two miles from the ancient colony of Ostia. The Roman port insensibly swelled to the size of an episcopal city, where the corn of Africa was deposited in spacious granaries for the use of the capital. As soon as Alaric was in possession of that important place, he summoned the city to surrender at discretion; and his demands were enforced by the positive declaration that a refusal, or even a delay, should be instantly followed by the destruction of the magazines, on which the life of the Roman people depended. The clamors of that people, and the terror of famine, subdued the pride of the senate; they listened, without reluctance, to the proposal of placing a new emperor on the throne of the unworthy Honorius; and the suffrage of the Gothic conqueror bestowed the purple on Attalus, prefect of the city. The grateful monarch immediately acknowledged his protector as master-general of the armies of the West; Adolphus, with the rank of count of the domestics, obtained the custody of the person of Attalus; and the two hostile nations seemed to be united in the closest bands of friendship and alliance.

The gates of the city were thrown open, and the new Emperor of the Romans, encompassed on every side by the Gothic arms, was conducted, in tumultuous procession, to the palace of Augustus and Trajan. After he had distributed the civil and military dignities among his favorites and followers, Attalus convened an assembly of the senate; before whom, in a formal and florid speech, he asserted his resolution of restoring the majesty of the republic, and of uniting to the Empire the provinces of Egypt and the East which had once acknowledged the sovereignty of Rome. Such extravagant promises inspired every reasonable citizen with a just contempt for the character of an unwarlike usurper, whose elevation was the deepest and most ignominious wound which the republic had yet sustained from the insolence of the Barbarians. But the populace, with their usual levity, applauded the change of masters. The public discontent was favorable to the rival of Honorius; and the sectaries, oppressed by his persecuting edicts, expected some degree of countenance, or at least of toleration, from a prince who, in his native country of Ionia, had been educated in the pagan superstition, and who had since received the sacrament of baptism from the hands of an Arian bishop.

The first days of the reign of Attains were fair and prosperous. An officer of confidence was sent with an inconsiderable body of troops to secure the obedience of Africa; the greatest part of Italy submitted to the terror of the Gothic powers; and though the city of Bologna made a vigorous and effectual resistance, the people of Milan, dissatisfied perhaps with the absence of Honorius, accepted, with loud acclamations, the choice of the Roman senate. At the head of a formidable army, Alaric conducted his royal captive almost to the gates of Ravenna; and a solemn embassy of the principal ministers, of Jovius, the prætorian prefect, of Valens, master of the cavalry and infantry, of the quæstor Potamius, and of Julian, the first of the notaries, was introduced, with martial pomp, into the Gothic camp. In the name of their sovereign, they consented to acknowledge the lawful election of his competitor, and to divide the provinces of Italy and the West between the two emperors. Their proposals were rejected with disdain; and the refusal was aggravated by the insulting clemency of Attalus, who condescended to promise that, if Honorius would instantly resign the purple, he should be permitted to pass the remainder of his life in the peaceful exile of some remote island. So desperate indeed did the situation of the son of Theodosius appear, to those who were the best acquainted with his strength and resources, that Jovius and Valens, his minister and his general, betrayed their trust, infamously deserted the sinking cause of their benefactor, and devoted their treacherous allegiance to the service of his more fortunate rival.

Astonished by such examples of domestic treason, Honorius trembled at the approach of every servant, at the arrival of every messenger. He dreaded the secret enemies who might lurk in his capital, his palace, his bed-chamber; and some ships lay ready in the harbor of Ravenna to transport the abdicated monarch to the dominions of his infant nephew, the Emperor of the East.

But there is a Providence—such at least was the opinion of the historian Procopius—that watches over innocence and folly; and the pretensions of Honorius to its peculiar care cannot reasonably be disputed. At the moment when his despair, incapable of any wise or manly resolution, meditated a shameful flight, a seasonable reinforcement of four thousand veterans unexpectedly landed in the port of Ravenna. To these valiant strangers, whose fidelity had not been corrupted by the factions of the court, he committed the walls and gates of the city; and the slumbers of the Emperor were no longer disturbed by the apprehension of imminent and internal danger. The favorable intelligence which was received from Africa suddenly changed the opinions of men and the state of public affairs. The troops and officers whom Attalus had sent into that province were defeated and slain; and the active zeal of Heraclian maintained his own allegiance and that of his people. The faithful Count of Africa transmitted a large sum of money, which fixed the attachment of the Imperial guards; and his vigilance in preventing the exportation of corn and oil introduced famine, tumult, and discontent into the walls of Rome.

The failure of the African expedition was the source of mutual complaint and recrimination in the party of Attalus; and the mind of his protector was insensibly alienated from the interest of a prince who wanted spirit to command, or docility to obey. The most imprudent measures were adopted, without the knowledge, or against the advice, of Alaric; and the obstinate refusal of the senate to allow, in the embarkation, the mixture even of five hundred Goths, betrayed a suspicious and distrustful temper, which, in their situation, was neither generous nor prudent. The resentment of the Gothic King was exasperated by the malicious arts of Jovius, who had been raised to the rank of patrician, and who afterward excused his double perfidy, by declaring, without a blush, that he had only seemed to abandon the service of Honorius, more effectually to ruin the cause of the usurper. In a large plain near Rimini, and in the presence of an innumerable multitude of Romans and Barbarians, the wretched Attalus was publicly despoiled of the diadem and purple; and those ensigns of royalty were sent by Alaric, as the pledge of peace and friendship, to the son of Theodosius.

The officers who returned to their duty were reinstated in their employments, and even the merit of a tardy repentance was graciously allowed; but the degraded Emperor of the Romans, desirous of life and insensible of disgrace, implored the permission of following the Gothic camp, in the train of a haughty and capricious Barbarian.

The degradation of Attalus removed the only real obstacle to the conclusion of the peace; and Alaric advanced within three miles of Ravenna, to press the irresolution of the Imperial ministers, whose insolence soon returned with the return of fortune. His indignation was kindled by the report that a rival chieftain, that Sarus, the personal enemy of Adolphus, and the hereditary foe of the house of Balti, had been received into the palace. At the head of three hundred followers, that fearless Barbarian immediately sallied from the gates of Ravenna; surprised, and cut in pieces, a considerable body of Goths; reëntered the city in triumph; and was permitted to insult his adversary by the voice of a herald, who publicly declared that the guilt of Alaric had forever excluded him from the friendship and alliance of the Emperor.

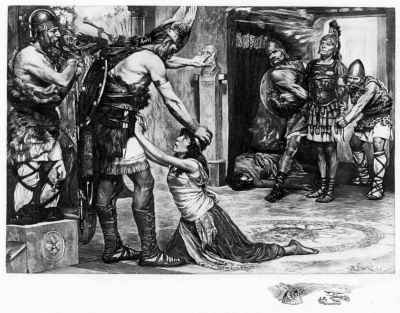

The crime and folly of the court of Ravenna were expiated a third time by the calamities of Rome. The King of the Goths, who no longer dissembled his appetite for plunder and revenge, appeared in arms under the walls of the capital; and the trembling senate, without any hopes of relief, prepared, by a desperate resistance, to delay the ruin of their country. But they were unable to guard against the secret conspiracy of their slaves and domestics; who, either from birth or interest, were attached to the cause of the enemy. At the hour of midnight the Salarian gate was silently opened, and the inhabitants were awakened by the tremendous sound of the Gothic trumpet. Eleven hundred and sixty-three years after the foundation of Rome, the Imperial city, which had subdued and civilized so considerable a part of mankind, was delivered to the licentious fury of the tribes of Germany and Scythia.

The proclamation of Alaric, when he forced his entrance into a vanquished city, discovered, however, some regard for the laws of humanity and religion. He encouraged his troops boldly to seize the rewards of valor, and to enrich themselves with the spoils of a wealthy and effeminate people; but he exhorted them, at the same time, to spare the lives of the unresisting citizens, and to respect the churches of the apostles St. Peter and St. Paul as holy and inviolable sanctuaries. Amid the horrors of a nocturnal tumult, several of the Christian Goths displayed the fervor of a recent conversion; and some instances of their uncommon piety and moderation are related, and perhaps adorned, by the zeal of ecclesiastical writers.

While the Barbarians roamed through the city in quest of prey, the humble dwelling of an aged virgin, who had devoted her life to the service of the altar, was forced open by one of the powerful Goths. He immediately demanded, though in civil language, all the gold and silver in her possession; and was astonished at the readiness with which she conducted him to a splendid hoard of massy plate, of the richest materials and the most curious workmanship. The Barbarian viewed with wonder and delight this valuable acquisition, till he was interrupted by a serious admonition, addressed to him in the following words: "These," said she, "are the consecrated vessels belonging to St. Peter; if you presume to touch them, the sacrilegious deed will remain on your conscience. For my part, I dare not keep what I am unable to defend." The Gothic captain, struck with reverential awe, despatched a messenger to inform the King of the treasure which he had discovered; and received a peremptory order from Alaric, that all the consecrated plate and ornaments should be transported, without damage or delay, to the church of the apostle.

From the extremity, perhaps, of the Quirinal hill, to the distant quarter of the Vatican, a numerous detachment of Goths, marching in order of battle through the principal streets, protected, with glittering arms, the long train of their devout companions, who bore aloft on their heads the sacred vessels of gold and silver; and the martial shouts of the Barbarians were mingled with the sound of religious psalmody. From all the adjacent houses a crowd of Christians hastened to join this edifying procession; and a multitude of fugitives, without distinction of age, or rank, or even of sect, had the good fortune to escape to the secure and hospitable sanctuary of the Vatican. The learned work, concerning the City of God, was professedly composed by St. Augustine, to justify the ways of Providence in the destruction of the Roman greatness. He celebrates, with peculiar satisfaction, this memorable triumph of Christ; and insults his adversaries by challenging them to produce some similar example of a town taken by storm, in which the fabulous gods of antiquity had been able to protect either themselves or their deluded votaries.

In the sack of Rome, some rare and extraordinary examples of Barbarian virtue have been deservedly applauded. But the holy precincts of the Vatican, and the apostolic churches, could receive a very small proportion of the Roman people; many thousand warriors, more especially of the Huns, who served under the standard of Alaric, were strangers to the name, or at least to the faith, of Christ; and we may suspect, without any breach of charity or candor, that in the hour of savage license, when every passion was inflamed, and every restraint was removed, the precepts of the Gospel seldom influenced the behavior of the Gothic Christians. The writers the best disposed to exaggerate their clemency have freely confessed that a cruel slaughter was made of the Romans; and that the streets of the city were filled with dead bodies, which remained without burial during the general consternation. The despair of the citizens was sometimes converted into fury; and whenever the Barbarians were provoked by opposition, they extended the promiscuous massacre to the feeble, the innocent, and the helpless. The private revenge of forty thousand slaves was exercised without pity or remorse; and the ignominious lashes which they had formerly received were washed away in the blood of the guilty or obnoxious families. The matrons and virgins of Rome were exposed to injuries more dreadful, in the apprehension of chastity, than death itself; and the ecclesiastical historian has selected an example of female virtue for the admiration of future ages.

A Roman lady, of singular beauty and orthodox faith, had excited the impatient desires of a young Goth, who, according to the sagacious remark of Sozomen, was attached to the Arian heresy. Exasperated by her obstinate resistance, he drew his sword, and, with the anger of a lover, slightly wounded her neck. The bleeding heroine still continued to brave his resentment and to repel his love, till the ravisher desisted from his unavailing efforts, respectfully conducted her to the sanctuary of the Vatican, and gave six pieces of gold to the guards of the church, on condition that they should restore her inviolate to the arms of her husband. Such instances of courage and generosity were not extremely common.

Avarice is an insatiate and universal passion; since the enjoyment of almost every object that can afford pleasure to the different tastes and tempers of mankind may be procured by the possession of wealth. In the pillage of Rome a just preference was given to gold and jewels, which contain the greatest value in the smallest compass and weight; but after these portable riches had been removed by the more diligent robbers, the palaces of Rome were rudely stripped of their splendid and costly furniture. The sideboards of massy plate, and the variegated wardrobes of silk and purple, were irregularly piled in the wagons, that always followed the march of a Gothic army. The most exquisite works of art were roughly handled or wantonly destroyed; many a statue was melted for the sake of the precious materials; and many a vase, in the division of the spoil, was shivered into fragments by the stroke of a battle-axe. The acquisition of riches served only to stimulate the avarice of the rapacious Barbarians, who proceeded, by threats, by blows, and by tortures, to force from their prisoners the confession of hidden treasure. Visible splendor and expense were alleged as the proof of a plentiful fortune; the appearance of poverty was imputed to a parsimonious disposition; and the obstinacy of some misers, who endured the most cruel torments before they would discover the secret object of their affection, was fatal to many unhappy wretches, who expired under the lash for refusing to reveal their imaginary treasures.

The edifices of Rome—though the damage has been much exaggerated—received some injury from the violence of the Goths. At their entrance through the Salarian gate they fired the adjacent houses to guide their march, and to distract the attention of the citizens; the flames, which encountered no obstacle in the disorder of the night, consumed many private and public buildings; and the ruins of the palace of Sallust remained, in the age of Justinian, a stately monument of the Gothic conflagration. Yet a contemporary historian has observed that fire could scarcely consume the enormous beams of solid brass, and that the strength of man was insufficient to subvert the foundations of ancient structures. Some truth may possibly be concealed in his devout assertion that the wrath of heaven supplied the imperfections of hostile rage; and that the proud Forum of Rome, decorated with the statues of so many gods and heroes, was levelled in the dust by the stroke of lightning.

Whatever might be the number of equestrian or plebeian rank who perished in the massacre of Rome, it is confidently affirmed that only one senator lost his life by the sword of the enemy. But it was not easy to compute the multitudes who, from an honorable station and a prosperous fortune, were suddenly reduced to the miserable condition of captives and exiles. As the Barbarians had more occasion for money than for slaves, they fixed a moderate price for the redemption of their indigent prisoners; and the ransom was often paid by the benevolence of their friends or the charity of strangers.

The captives, who were regularly sold either in open market or by private contract, would have legally regained their native freedom, which it was impossible for a citizen to lose or to alienate. But as it was soon discovered that the vindication of their liberty would endanger their lives; and that the Goths, unless they were tempted to sell, might be provoked to murder their useless prisoners; the civil jurisprudence had been already qualified by a wise regulation that they should be obliged to serve the moderate term of five years, till they had discharged by their labor the price of their redemption.

The nations who invaded the Roman Empire had driven before them, into Italy, whole troops of hungry and affrighted provincials, less apprehensive of servitude than of famine. The calamities of Rome and Italy dispersed the inhabitants to the most lonely, the most secure, the most distant places of refuge. While the Gothic cavalry spread terror and desolation along the sea-coast of Campania and Tuscany, the little island of Igilium, separated by a narrow channel from the Argentarian promontory, repulsed, or eluded, their hostile attempts; and at so small a distance from Rome, great numbers of citizens were securely concealed in the thick woods of that sequestered spot. The ample patrimonies, which many senatorian families possessed in Africa, invited them, if they had time, and prudence, to escape from the ruin of their country, to embrace the shelter of that hospitable province. The most illustrious of these fugitives was the noble and pious Proba, the widow of the prefect Petronius. After the death of her husband, the most powerful subject of Rome, she had remained at the head of the Anician family, and successively supplied, from her private fortune, the expense of the consulships of her three sons. When the city was besieged and taken by the Goths, Proba supported, with Christian resignation, the loss of immense riches; embarked in a small vessel, from whence she beheld, at sea, the flames of her burning palace, and fled with her daughter Læta, and her granddaughter, the celebrated virgin Demetrias, to the coast of Africa. The benevolent profusion with which the matron distributed the fruits, or the price, of her estates, contributed to alleviate the misfortunes of exile and captivity. But even the family of Proba herself was not exempt from the rapacious oppression of Count Heraclian, who basely sold, in matrimonial prostitution, the noblest maidens of Rome to the lust or avarice of the Syrian merchants.

The Italian fugitives were dispersed through the provinces, along the coast of Egypt and Asia, as far as Constantinople and Jerusalem; and the village of Bethlehem, the solitary residence of St. Jerome and his female converts, was crowded with illustrious beggars of either sex, and every age, who excited the public compassion by the remembrance of their past fortune. This awful catastrophe of Rome filled the astonished Empire with grief and terror. So interesting a contrast of greatness and ruin disposed the fond credulity of the people to deplore, and even to exaggerate, the afflictions of the queen of cities. The clergy, who applied to recent events the lofty metaphors of oriental prophecy, were sometimes tempted to confound the destruction of the capital and the dissolution of the globe.

There exists in human nature a strong propensity to depreciate the advantages, and to magnify the evils, of the present times. Yet, when the first emotions had subsided, and a fair estimate was made of the real damage, the more learned and judicious contemporaries were forced to confess that infant Rome had formerly received more essential injury from the Gauls than she had now sustained from the Goths in her declining age. The experience of eleven centuries has enabled posterity to produce a much more singular parallel, and to affirm with confidence that the ravages of the Barbarians, whom Alaric had led from the banks of the Danube, were less destructive than the hostilities exercised by the troops of Charles V, a Catholic prince, who styled himself Emperor of the Romans.

The Goths evacuated the city at the end of six days, but Rome remained above nine months in the possession of the Imperialists, and every hour was stained by some atrocious act of cruelty, lust, and rapine. The authority of Alaric preserved some order and moderation among the ferocious multitude which acknowledged him for their leader and king; but the constable of Bourbon had gloriously fallen in the attack of the walls; and the death of the general removed every restraint of discipline from an army which consisted of three independent nations, the Italians, the Spaniards, and the Germans.

The retreat of the victorious Goths, who evacuated Rome on the sixth day, might be the result of prudence; but it was not surely the effect of fear. At the head of an army encumbered with rich and weighty spoils, their intrepid leader advanced along the Appian way into the southern provinces of Italy, destroying whatever dared to oppose his passage, and contenting himself with the plunder of the unresisting country.

Above four years elapsed from the successful invasion of Italy by the arms of Alaric to the voluntary retreat of the Goths under the conduct of his successor Adolphus; and during the whole time they reigned without control over a country which, in the opinion of the ancients, had united all the various excellences of nature and art. The prosperity, indeed, which Italy had attained in the auspicious age of the Antonines had gradually declined with the decline of the Empire. The fruits of a long peace perished under the rude grasp of the Barbarians; and they themselves were incapable of tasting the more elegant refinements of luxury which had been prepared for the use of the soft and polished Italians. Each soldier, however, claimed an ample portion of the substantial plenty, the corn and cattle, oil and wine that was daily collected and consumed in the Gothic camp; and the principal warriors insulted the villas and gardens, once inhabited by Lucullus and Cicero, along the beauteous coast of Campania. Their trembling captives, the sons and daughters of Roman senators, presented, in goblets of gold and gems, large draughts of Falernian wine to the haughty victors, who stretched their huge limbs under the shade of plane trees, artificially disposed to exclude the scorching rays and to admit the genial warmth of the sun. These delights were enhanced by the memory of past hardships; the comparison of their native soil, the bleak and barren hills of Scythia, and the frozen banks of the Elbe and Danube added new charms to the felicity of the Italian climate.[18]

Whether fame or conquest or riches were the object of Alaric, he pursued that object with an indefatigable ardor which could neither be quelled by adversity nor satiated by success. No sooner had he reached the extreme land of Italy than he was attracted by the neighboring prospect of a fertile and peaceful island. Yet even the possession of Sicily he considered only as an intermediate step to the important expedition which he already meditated against the continent of Africa.

The whole design was defeated by the premature death of Alaric, which fixed, after a short illness, the fatal term of his conquests. The ferocious character of the Barbarians was displayed in the funeral of a hero whose valor and fortune they celebrated with mournful applause. By the labor of a captive multitude, they forcibly diverted the course of the Busentinus, a small river that washes the walls of Consentia. The royal sepulchre, adorned with the splendid spoils and trophies of Rome, was constructed in the vacant bed; the waters were then restored to their natural channel, and the secret spot where the remains of Alaric had been deposited was forever concealed by the inhuman massacre of the prisoners who had been employed to execute the work.

The personal animosities and hereditary feuds of the Barbarians were suspended by the strong necessity of their affairs, and the brave Adolphus, the brother-in-law of the deceased monarch, was unanimously elected to succeed to his throne. The character and political system of the new King of the Goths may be best understood from his own conversation with an illustrious citizen of Narbonne; who afterward, in a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, related it to St. Jerome, in the presence of the historian Orosius. "In the full confidence of valor and victory, I once aspired (said. Adolphus) to change the face of the universe; to obliterate the name of Rome; to erect on its ruins the dominion of the Goths; and to acquire, like Augustus, the immortal fame of the founder of a new empire. By repeated experiments I was gradually convinced that laws are essentially necessary to maintain and regulate a well-constituted state; and that the fierce, untractable humor of the Goths was incapable of bearing the salutary yoke of laws and civil government. From that moment I proposed to myself a different object of glory and ambition; and it is now my sincere wish that the gratitude of future ages should acknowledge the merit of a stranger who employed the sword of the Goths, not to subvert, but to restore and maintain, the prosperity of the Roman Empire." With these pacific views, the successor of Alaric suspended the operations of war, and seriously negotiated with the Imperial court a treaty of friendship and alliance. It was the interest of the ministers of Honorius, who were now released from, the obligation of their extravagant oath, to deliver Italy from the intolerable weight of the Gothic powers; and they readily accepted their service against the tyrants and Barbarians who infested the provinces beyond the Alps. Adolphus, assuming the character of a Roman general, directed his march from the extremity of Campania to the southern provinces of Gaul. His troops, either by force or agreement, immediately occupied the cities of Narbonne, Toulouse, and Bordeaux; and though they were repulsed by Count Boniface from the walls of Marseilles, they soon extended their quarters from the Mediterranean to the ocean. The oppressed provincials might exclaim that the miserable remnant which the enemy had spared was cruelly ravished by their pretended allies; yet some specious colors were not wanting to palliate, or justify, the violence of the Goths. The cities of Gaul, which they attacked, might perhaps be considered as in a state of rebellion against the government of Honorius; the articles of the treaty or the secret instructions of the court might sometimes be alleged in favor of the seeming usurpations of Adolphus; and the guilt of any irregular, unsuccessful act of hostility might always be imputed, with an appearance of truth, to the ungovernable spirit of a Barbarian host, impatient of peace or discipline. The luxury of Italy had been less effectual to soften the temper than to relax the courage of the Goths; and they had imbibed the vices, without imitating the arts and institutions, of civilized society.